In 1966, the United States Air Force was tasked with providing the military forces of the Kingdom of Laos with covert air support through a series of clandestine operations in conjunction with the CIA. Perhaps the most famous air unit of the Vietnam War, the Raven Forward Air Controllers, were born out of this covert effort.

1. Why Does it Matter:

Numerous misconceptions, misnomers and misattributions are prevalent over the nature of Project 404. The US Air Force and CIA are partly to blame for this confusion. The project and operations changed codenames in a seemingly arbitrary fashion. The scope of the project ballooned and contracted year by year. The detailed specifics of operations are not well-circulated or fully recorded. As such, this chapter of the US Air Force’s history is difficult to unpack and assess.

Nonetheless, this chapter is an excellent case study of the birth of modern counterinsurgency (COIN) air operations as we recognize them today. There are valuable lessons to be learned from the history of Project 404 both for policymakers interested in COIN operations and even for a casual reader of military history.

2. Prelude to the Secret War:

In 1954, the United States, France, China and the Soviets gathered together in Geneva to settle on a lasting solution to the borders of East Asia. Three successor states formed out of the body of French Indochina: Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. Yet, the Geneva Accords of 1954 did nothing to settle the spectre of war in Southeast Asia.

2.1 Strategic Gamble:

When the Kennedy Administration came to power in 1961, the Cold War was beginning to acquire a dangerous, atomically charged odour. As Eisenhower departed the White House, he made it clear to the incoming President that the Kingdom of Laos was critical for securing an anti-Soviet front in Indochina. Kennedy disagreed and took a different approach [source]. Kennedy based his decision on two salient facts about the relative strategic values of Laos and Vietnam.

The first was the apparent resiliency of the regime of South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem. Diem had, up until that point, clung to power since 1954. The factions governing Laos on the other hand were a patchwork of mortal enemies, a political Frankenstein of sorts. Second, Kennedy believed that the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) would rally behind South Vietnam in an anti-Soviet front. Both of these assumptions proved to be totally wrong [source].

Contrary to Kennedy’s high opinions of President Diem, Diem spent the better part of the late 1950s and early 1960s antagonizing Vietnam’s Buddhist population. This led to his arrest and execution during a military coup in November 1963. To quote John Schlight: “The Kennedy administration had discovered that Diem possessed an almost limitless capacity to disappoint” [source]. Additionally, country to Kennedy’s high opinions of SEATO, two members of the organization refused to support the US invasion, of France and Pakistan. The organization collapsed following the US retreat from Indochina [source].

2.2 Unassuming at First Sight:

Laos is unassuming at first sight. Its internal geography consists of unbroken jungles and humid highlands. A spinal cord of in-traversable mountains runs the length of the country, covering 70% of Laotian territory [source]. It is easy to overlook on a map, a historically neglected region which only recently liberated itself from Japanese and French occupation. Countries such as Egypt, India, or Panama generally found themselves in the cross-hairs of larger global powers by accidents of geography. In the case of both Panama and Egypt, favourable terrain allowed for the construction of artificial strategic waterways. In the case of India, climatic patterns facilitated the production of valuable cash crops. Laos on the other hand, did not boast any of these bonuses. Laos fell into the sights of the Soviet Union and the United States by mere virtue of its proximity to the anti-communist struggle in Vietnam [source].

In 1958, North Vietnamese regulars invaded Laos with the intention of supporting the Pathet Lao insurgency. Several villages were occupied near Sepon. However, the hostilities only began in earnest in July of 1959 [source]. The North Vietnamese would initiate attacks against Royal Laotian troops along the line of contact and then retreated. This allowed Pathet Lao insurgents to assume the forward position, thereby concealing the North Vietnamese retreat and involvement in the fighting [source].

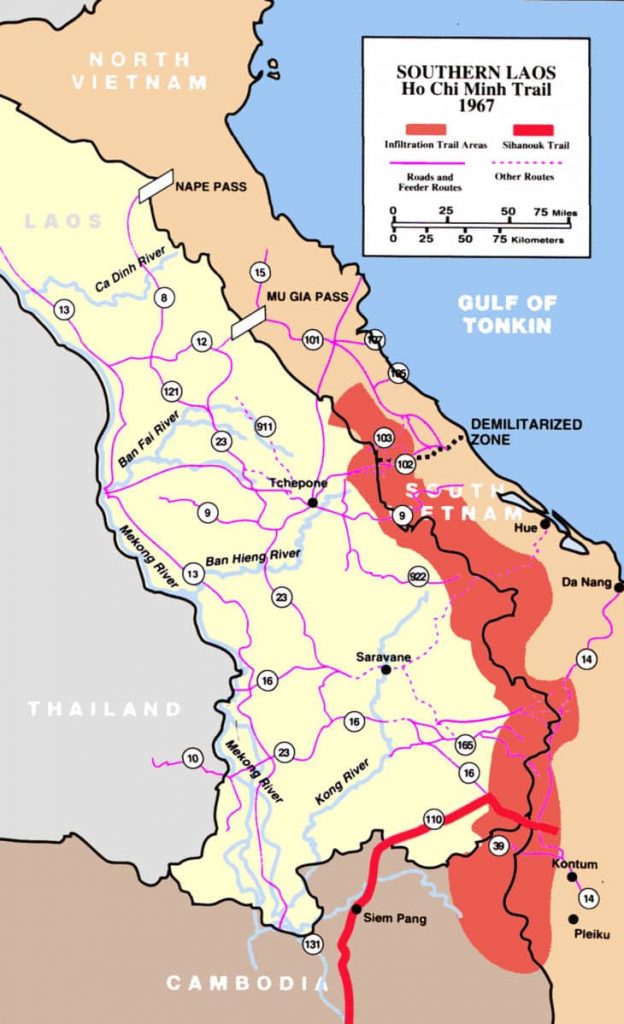

The surreptitious incursions into Laos by the North Vietnamese were the beginning of the Ho Chi Minh Trail (HCMT), a series of land routes which stretched from the sea to the Laotian interior and then into South Vietnam [source]. The HCMT was the logistical lifeline of the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese regular units operating in the vicinity of Saigon, numbering in the range of 15,000 [source]. In order to win the war in Vietnam, the United States soon discovered it would need to address the use of Laos as a logistical staging ground for the Viet Cong.

This is a major misconception about the Secret War. The United States did not unilaterally violate the provisions of the treaty which declared Laos a neutral party in 1962. The North Vietnamese were already engaged in Laos four years prior to the declaration of neutrality. The Viet Minh had also assisted the Pathet Lao in coming dangerously close to the royal capital of Luang Prabang in 1953 [source].

2.3 Chinese and Soviet Support for the Pathet Lao

Beijing openly encouraged the prosecution of a ‘people’s war’ strategy in the country and rendered enormous amounts of material support to the Pathet Lao through supply chains in Yunnan province [source]. Soviet and Chinese specialists were also present in Laos, providing training to the Pathet Lao [source]. A 1963 CIA intelligence memorandum outlines the completion of an all-weather road from Meng La to Phong Saly in northern Laos. Soviet aid to the Pathet Lao was discovered by sheer accident. On the 16th of December, 1960, VC-47 piloted by Col. Butler Toland was on a routine flight from Luang Prabang to Vientiane. Col. Toland suddenly noticed a Soviet IL-14 circling over Vang Vieng. Col. Toland captured an image of the IL-14 para dropping supplies to communist positions. The next day, the US officially condemned Soviet support for the Pathet Lao [source].

CIA files recorded a history of Chinese infrastructure projects across northern Laos and the developing network of roads and bridges linking Yunnan with Pathet Lao-controlled territory [source]. Phong Say was home to Chinese military officers masquerading as diplomatic staff, who were present in Phong Saly since at least November of 1961 [source]. Besides, there was a widespread belief in North Vietnam that Laos was a historical part of Vietnam and lost territory [source]. In that view, the border between Laos and Vietnam meant very little.

There are parallels between the Viet Cong’s reliance on Chinese aid delivered through Laos and the use of Pakistan by the Taliban for strategic cover. Insurgencies are at a disadvantage per their lack of an industrial base, well-guarded supply lines and a home base of operations. Like the Safed Koh range which straddles Pakistan and Afghanistan, the Laotian highlands provided ample cover to the Pathet Lao and Viet Cong. Like the porous border of the Durand Line in Afghanistan, the HCMT would snake through these mountain edifices and come to frustrate the US effort in South Vietnam.

3. Humble Beginnings

The United States set up a Military Advisory Assistance Group (MAAG) as early as 1950 to assist French colonial forces during the First Indochina War [source]. Following the French departure, the MAAG was assigned to South Vietnam in an effort to train and build up the nascent republic’s military capacity. While South Vietnam enjoyed the benefits of support from the MAAG, the equivalent advisory group in Laos, the Programs Evaluation Office (PEO), fared poorly and made do with little resources. This changed upon the arrival of John Heintges in September of 1958 [source].

Having recently left the army, Heintges was assigned to the PEO and rapidly was made aware of the sorry state of the outfit. Heintges reported back to Washington with an alarming state of affairs. The White House heeded his warnings and agreed to step up military assistance to the Royal Lao government. Because of the provisions of the Geneva agreement, the US was unable to provide this aid directly [source].

A front company was organized, the Eastern Construction Company, and was primarily staffed by Filipino military personnel who were trained by the US in COIN operations during the Huk insurgency [source]. An air of total operational secrecy shrouded the increased presence of US military advisors. No open displays of military courtesies were allowed, civilian-style clothing was issued to the US Army officers and the orders issued to the staff were deliberately vague or even inaccurate [source].

3.1 Operation Hotfoot

In July 1959, the PEO became the conduit for Operation Hotfoot. Heintges was adamant about the need for additional military assistance, and he received this in the form of US Special Forces. Teams of Green Berets were deployed to Laos with US Embassy identifiers and were issued temporary duty orders so that their presence in the country would not be recorded in the official troop count [source].

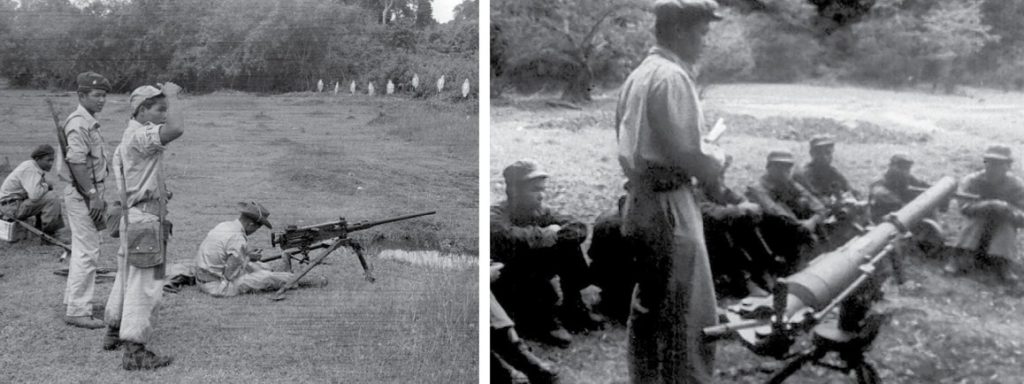

The Green Berets trained the Royal Lao government forces on COIN tactics and on the use of small arms and heavy weapons. Throughout 1959-1961, North Vietnamese regulars engaged the Royal Lao forces on numerous occasions. On the other hand, the American military advisors were seldom if ever exposed to danger [source]. Despite the skills and dedication of US special operations teams, the difficulties presented by regular Vietnamese incursions along the HCMT highlighted the need for the introduction of air power into the equation.

The PEO had some limited experience with air operations. In an effort to sway the direction of the 1958 national assembly elections, the CIA organized Operation Booster Shot. The objective was to convince the Laotian peasantry to vote for US-sponsored politicians [source]. Aid and vaccines were the incentive for them to do so. The Royal Lao Air Force was wholly unequipped for this task, so the US Air Force was called in to assist in the delivery of aid. The CIA’s front airline, Air America, stepped in to help as well [source].

3.2 Air America at Work

Air America acted as the air arm of Hotfoot from the beginning. In November of 1959 for instance, Air America C-46s flew missions into Khang Khay, where Hotfoot teams were busy constructing weapons ranges and training facilities for Hmong rebels [source]. The aid drives, although completed exclusively by Air America, were organized through the PEO, giving the staff valuable experience in the complexities of air operations in Laos [source].

Air America pilots had extensive knowledge of the geography and hazards of the Laotian airspace. A common occurrence was the inclement weather in the mountains. An airfield could be flooded by rainwater and shrouded in thick fog, where not even a matter of miles away, another airfield could be baking in the sun. Air America pilots offered experienced pilots familiar with the landscape [source].

The PEO itself managed to secure 10 T-6 light attack aircraft and 13 C-47s for the Royal Laotian Air Force. T-28D Trojans were also employed. Philippine aircraft technicians were brought in to service the planes, and when 2 T-6s were lost to ground fire, Thailand quickly replaced the 2 units [source]. Funding for this operation was provided by the US Embassy in Vientiane, with funds earmarked for the Royal government on the understanding that the Pathet Lao would never be allowed to form a coalition government with Royalist forces.

Operation Hotfoot came to an end as a result of this pre-condition. Dissatisfied with the Royal government and the prohibition on cooperation with the Pathet Lao, General Kong Le led a rebellion of the Laotian paratrooper regiments, overthrowing the government in 1960 [source].

3.3 Operation White Star

Kong Le’s surprise military coup in 1960 upended the arrangements made by Hotfoot throughout the late 1950s. The US was compelled to become engaged in a far more direct fashion than it previously had anticipated. As such, Hotfoot metamorphosed into Operation White Star [source].

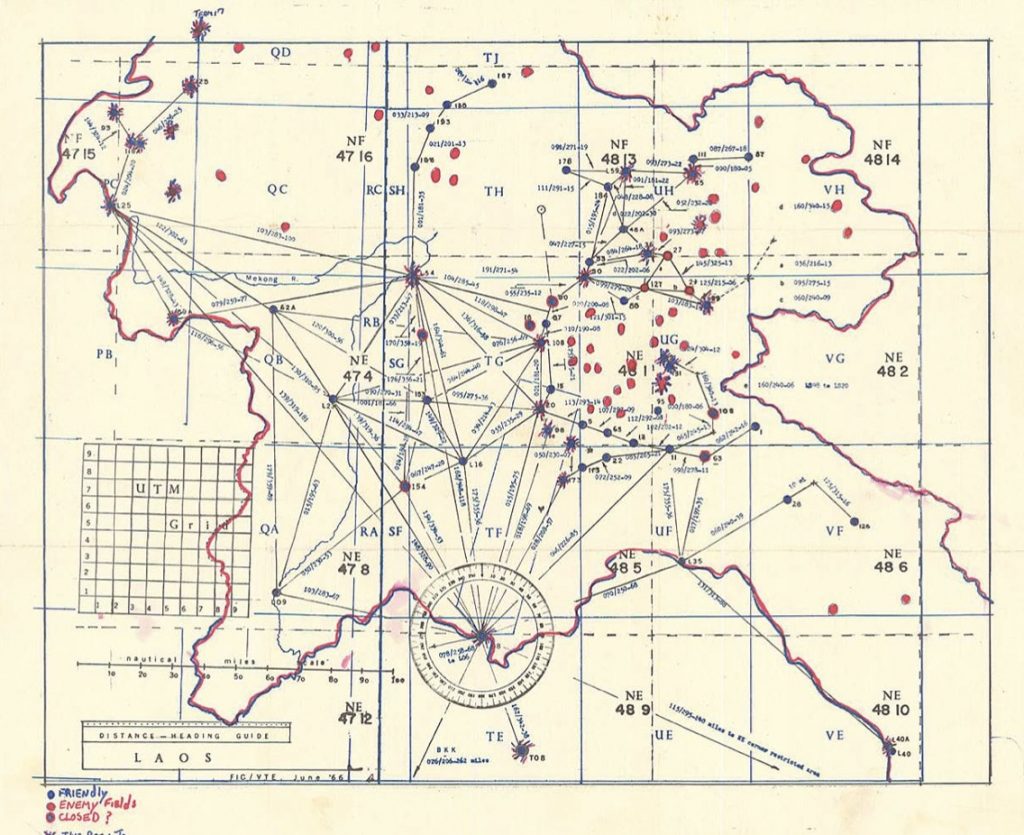

Operation White Star greatly increased the US footprint in Laos by expanding the PEO and establishing what is colloquially known as Lima Sites. The term Lima Sites is the phonetic reading of ‘LS’, initially intended to stand for Laos Strips. They were first envisioned as Victor Strips, the equivalent type of landing strip in Vietnam. Built by local labour, these sites were small mountaintop bases with runways no longer than 600 ft in length. The runways were often dangerous to land on and susceptible to becoming a strip of mud. Throughout the time of Hotfoot and White Star and the US Army Green Beret rotations, roughly 40 such facilities were in use. By 1973, nearly 400 were constructed [source].

White Star came to a close in 1961 as the PEO was upgraded to a MAAG. Kennedy may have been reassessing his original inclinations about the relative importance of Vietnam and Laos. His thinking also seems to have changed about the best manner to approach the issue. After all, the Bay of Pigs fiasco demonstrated to Kennedy that a rag-tag group of disaffected exiles did not have the necessary discipline to conduct irregular warfare [source].

The deteriorating situation in Laos following Kong Le’s coup and the escalation of hostilities with communist insurgents in Vietnam also likely played into Kennedy’s thinking. It is not possible to know the exact line of thought behind the President’s decision to elevate the PEO to a full-fledged MAAG, but in any case, the situation in Laos was beginning to change [source].

3.4 The Necessity of Forward Air Control

The states which were parties to the 1954 Geneva Accords reconvened again in Geneva in 1962 to finalize a settlement to the status of Laos. The Declaration on the Neutrality of Laos established a fragile triumvirate of nationalist, communist and neutralist forces as the ruling body of the kingdom. More importantly, it forced the neutral status of the kingdom. It would neither camp in the Soviet, Chinese or American sphere. The North Vietnamese, although signatories of the treaty, made no effort to actually honour those commitments. The invasion force which had captured Laotian border villages in 1958 was never withdrawn [source].

Declassified CIA files demonstrate the role North Vietnamese troops played in aiding the Pathet Lao. In 1963, two battalions of North Vietnamese troops joined roughly 2,500 Pathet Lao insurgents just east of the Plain of Jars, a historically important region which also happened to be strategically vital [source]. The plains were the only area sufficiently flat enough on which to land light aircraft. The loss of the plains is what prompted the CIA to utilize Air America to aid in smuggling Hmong opium shipments to and from General Vang Pao’s headquarters in Long Tien [source].

In light of the presence of North Vietnamese forces in the country, Prince Souvanna Phouma, the Laotian Prime Minister turned to the United States for additional assistance. He requested an air campaign, targeting the Pathet Lao forces, on the condition that the airstrikes remain unknown to the wider public [source]. Operation Barrel Roll and Operation Steel Tiger were initiated in 1964, targeting the north and south of Laos respectively.

The operations consisted of airstrikes of Pathet Lao positions and coincidently targeted areas where the HCMT happened to transverse. Conducted by interdiction aircraft such as the F-100 and F-105, the strikes were inaccurate and often resulted in civilian casualties [source]. The infamous “Sam Neua Incident” in 1964 illustrated the dangers of conducting bombing runs over civilian areas. Portions of the town of Sam Neua were mistakenly targeted after the USAF pilots attempted to strike 105mm gun positions [source].

These unfortunate incidents also highlight a recurring phenomenon of COIN operations, at least those conducted exclusively from the air. By the very nature of insurgencies, targeting fixed positions or a static line of contact is nearly impossible. Insurgents can rapidly spread out over a wide area, rendering areal bombardment essentially worthless and cost-ineffective [source]. Moreover, using a highly advanced and very expensive jet to kill a dozen or so insurgents is fantastically inefficient. Given the fact that US bombers were conducting nearly 300 sorties a day, this would greatly inflate the eventual bill [source]. A friendly fire incident in 1965 at Moung Phalane resulted in a suspension of the airstrikes until a proper forward air control system (FAC) could be established [source].

4. Air Commandos and Call Sign Butterfly

The very first ‘air commandos’ were a product of the Second World War. First activated in India in 1943, the program was initially dubbed Project 9. Its objective was to invade Japanese-occupied Burma by air. By occupying Burma, Japanese troops had severed the supply link, known as the Burma Road, which fed Chang Kai-Shek’s Nationalist army in mainland China [source].

The Air Commandos would insert groups of irregular troops known as Chindists deep behind enemy lines using CG-4A Waco and TG-5 Training gliders. Despite enormous obstacles and loss, the Chindists halted the advance of Japanese troops in Burma. The operation was a total success. Japanese generals stated in post-war interviews that “the penetration of the airborne force into Northern Burma caused the failure of the Army plan” and that the Air Commando operation “eventually became one of the reasons for the total abandonment of Northern Burma” [source].

4.1 Operation Water Pump and the 58th SOW

The concept of deep penetration teams clearly proved its own worth. The Air Commando units of the USAF were first deployed into Vietnam under the umbrella of Operation Water Pump, attacked by the 58th Special Operations Wing. Water Pump had a three-pronged aim in Laos [source]:

- Develop Laotian air power with light COIN aircraft

- Successfully halt the infiltration of Vietnamese and Pathet Lao forces

- Develop search and rescue (SAR) capabilities for USAF bombing runs over Laos

With the departure of the Green Berets in 1962, the US had no means of conducting SAR operations in Laos. This role was largely undertaken by Air America and the 1st Air Commando Wing (ACW) stationed in Udorn, Thailand. This would need to be addressed. Moreover, the system developed for artillery strikes and marking targets was ineffective and primitive.

Smoke signals were used by Laotian ground forces to identify the friendly positions. A forward air guide (FAG) would communicate with the aircraft and “talk” the pilots towards the intended targets. Air America aircraft were sometimes deployed to assist in identifying targets [source]. Laotian T-28 pilots would then make their strafing or bombing runs. On a few occasions, ground crews would use targeting panels and arrows to display the direction of the intended fire [source]. There were a number of serious limitations to these methods [source]:

- Using smoke signals gave away friendly positions to enemy soldiers

- Establishing a line of sight over the jungle and mountains of Laos was a nearly impossible task for ground-based crews

- The imprecise nature of these methods caused an unacceptable level of collateral damage to friendly forces

- CIA-operated aircraft lacked appropriate radio communication systems to contact ground teams

As the rate of interdiction flights above the HCMT increased with Operations Barrel Roll and Steel Tiger, the lack of adequate FAC was enormously problematic. Air Commandos were called to provide FAC with the assistance of Air America aircraft, whose pilots had prior experience in directing artillery fire for Royal Lao troops [source]. Consisting mostly of T-28 attack aircraft, U-6 Beavers, U-17 and at least one Aero Commander 660, the aircraft was flown by non-commissioned officers who were themselves Air Commandos assigned to Operation Water Pump [source].

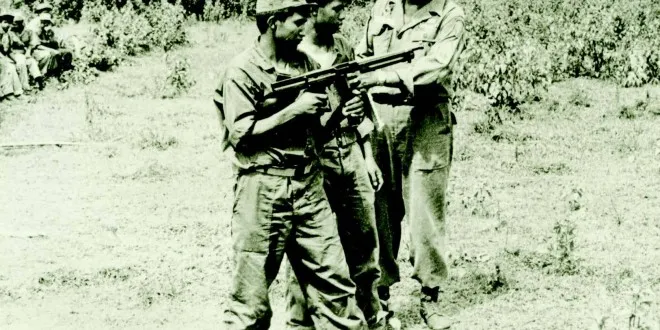

Sgt John A. “Spider” Webb and Sgt Wayne Hoke, under the command of Captain Robert T. “Bob” Schneidenbach, recycled older methods used during the Korean War to develop the FAC capabilities of the Royal Lao forces and those of General Vang Pao. Ground units would no longer need to rely on imprecise and costly FAG controllers to mark targets. Known as Mosquitoes during the Korean War, the non-commissioned officers acquired a new callsign, Butterfly [source].

The term Butterfly originated not from the US Air Force or CIA, but from Laotian bar girls. SSgt. James Stanford recounted the bizarre manner by which he and his colleagues came by their names:

Water Pump personnel adopted their monikers and wore them well throughout the war. General Vang Pao was assigned a Butterfly team consisting of Capt John Teague and Sgt Stanley Monnie in July of 1965. Teague and Monnie, along with a CIA operative known as Tony Poe selected targets on the Plain of Jars from an Air America helicopter. Teague (callsign Cherokee) bears several military distinctions. He was the first to use an AR-15 and rifle-attached grenade launcher in combat [source]. He was also entrusted with a large degree of discretion by the Laotians and the US Embassy in Vientiane. In his words:

Butterflies were deployed for extended periods with their Laotian colleagues and a Laotian ground commander. Often, an interpreter was included onboard to translate between he FAC and Thai T-28 pilots. The Butterfly would carry an FM PRC-25, a backpack radio with an extendable antenna, in order to radio ground teams. Where possible, the FAC would contact the Airborne Battlefield Command and Control Center (ABCCC) and request USAF airstrikes [source]. This was rarely done as there were seldom any means of marking the intended targets for US jets. Smoke grenades were deployed in an effort to mark targets, but this inaccurate method was liable to cause a friendly fire incident [source]. Moreover, according to one Raven later in the war, the system required a high degree of improvisation:

The Butterflies would instead resort to the older method of talking the aircraft onto the target by describing landmarks. This required the Butterflies to be colorful in their descriptions of the target, the point of overly laden on details [source].

Although above the fray of the actual fighting, the Butterflies were not totally obscured from danger. On the 18th of May, 1966, Airman 1st Class Andre R. “Andy” Guillet and Capt Lee D. Harley were operating above section of jungle in an O-1 Bird Dog. Another O-1 nearby noticed enemy troop and vehicle movement below and the two aircraft began marking targets for airstrikes.

The pilot of the other O-1 reported that Harley and Guillet were last seen crashing into the forest canopy, and having received no emergency transmission, the pilots assumed that the O-1 was struck by ground fire and severally damaged. A SAR operation was immediately launched, in the process of which an F-4 was shot down. It’s crew manage to eject and survived the crash [source].

4.2 From Butterfly to Raven

Despite the success and sacrifices of the Butterfly controllers, and despite the respect they commanded among Laotian forces, the Butterfly project was terminated rather unceremoniously. In 1967, the 58th SOW was visited by none other than the deputy commander for air operations in Vietnam, General William Momyer. Momyer was a highly decorated WWII flying ace who rose through the ranks after the war [source].

Momyer has a generally controversial past and legacy. He is often accused of harboring racial animosity towards the Tuskegee Airmen and is often credited with writing a racially charged report recommending the 99th be removed from combat and assigned to costal patrol. This is a misattribution, it was Momyer’s superior General Edwin J. House, who penned racially inappropriate notes into the margins of Momyer’s reports [source]. While Momyer may not have been a racist, he certainly was an elitist.

Despite demonstrable evidence to the contrary, Momyer took exception to the sort of aircraft in use by the Butterflies. He was a proponent of an all-jet air force, believing that a jet aircraft was superior in every sense, for any purpose [source]. Momyer’s thinking reveals a mentality formed by the circumstances of the Second World War, but totally unsuited for post-war COIN operations. The A-1 Skyraiders, the T-28 Trojans and various other aircraft had a highly successful track record of interdiction along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Propeller aircraft could loiter for longer, were easier to use, train on and maintain [source]. An inexperienced Royal Laotian Air Force pilot had absolutely no chance of successfully learning to pilot an F-100 or an A-37. Momyer’s vision of an all-jet air force ran contrary to the needs and complexities of COIN operations in Laos.

Momyer met with the commanding officer of the 58th, Col. Aderholt at Nakhon Phanom. Aderholt had a habit of popping up at critical moments of American espionage during the Cold War. Then Major Aderholt was intimately involved in supplying Tibetan rebels in the 1950s and in the prelude to the Bay of Pigs operation in the early 1960s [source]. He also was instrumental in CIA covert operations in Indonesia and flew a C-47 in Korea, inserting CIA operatives behind enemy lines [source]. Now, he would inadvertently give birth to one of the most celebrated covert air units in US Air Force history.

Aderholt attempted to explain the situation with poor FAC procedures, illustrating that O-1s had little range to reach beyond the operational areas required by the movement of insurgents. As Aderholt explained the failings of the Butterfly system and the reliance on Air America pilots, Momyer seemed perplexed as to what the system exactly entailed. As Aderholt later recounted [source]:

“Momyer asked, “Who’s FACing my airplanes?”

I said, “I’ve got a bunch of enlisted Commandos up there.”

Momyer hit the roof! He exclaimed, “What? Who is flying the airplanes?”

I said, “Air America pilots in their airplanes,” as Momyer jumped up and down.

He said, “That will cease. I’ll take care of that!”

“Momyer told his Director of Operations, “These guys are up there FACing my aeroplanes, and they’re not qualified, and they’re not pilots, and I want that ceased.”

Momyer clearly had no interest in the fact that the enlisted men, whose presence in the sky incensed him so much, had established excellent working relations with Laotian ground teams and military leadership. He was also wrong as many of them were in fact pilots [source]. The mere fact of their rank was beyond the pale for him and the project was terminated. At the very least, it seems as if Aderholt managed to convince Momyer of the value of propeller aircraft for COIN operations.

Momyer insisted that FACs would now be rated flight officers, volunteer jet pilots who would have the required skills to direct other jet pilots onto the targets. Momyer’s new revamped FAC program ‘Steve Canyon’, would be staffed exclusively by officers [source]. The call sign Butterfly would also be changed. And so the Ravens were born.

5. Palace Dog, the Ravens and Project 404:

The last Butterflies, Sergeant Carlyle and Airman Kosh, last flew in April 1967 [source]. Capt James Cain, formerly known as Butterfly 70, would become the first Raven, now flying under the callsign Raven 41 [source]. Col Paul A. Pettigrew is considered the father of the term, referring to the folklore of Nordic mythology where Odin’s ravens circle the battlefield from above [source].

In May 1968, the Joint Chiefs of Staff approved Project 404. The project was an attempt to permanently staff the military attache contingent at the US Embassy in Laos. William Sullivan, the US Ambassador to Laos, sought to fill those ranks with military professionals with past special operations experience [source]. Project 404 consisted of over 100 military personnel and at least 5 civilians [source]. The purpose of the project was to assess the effectiveness of the aid which was being delivered to Laos. They were under the direct command of Ambassador Sullivan and divided into four types of observers.

- LSA’s, or logistic, support and administration observers were drawn from all branches of the military. They provided support for PSYOPS, COIN and interrogation efforts [source].

- ARMA’s were army observers working in 3-5 man teams in various military regions throughout Laos. They acted as military advisors and were often accompanied by special forces teams [source].

- AIRAs were US Air Force officers deployed as dedicated advisors to the Royal Lao Air Force training mission in Udorn, Thailand. The officers would fly to and from Thailand and Laos on a daily basis. They were responsible for the AC-47 program of the Royal Lao Air Force. AIRA activities were classified under the codename Palace Dog [source].

- The Ravens were grouped under Project 404 in October of 1966 [source].

The collective grouping of Project 404 and the Ravens was known simply as Palace Dog [source].

5.1 The Ravens at Work:

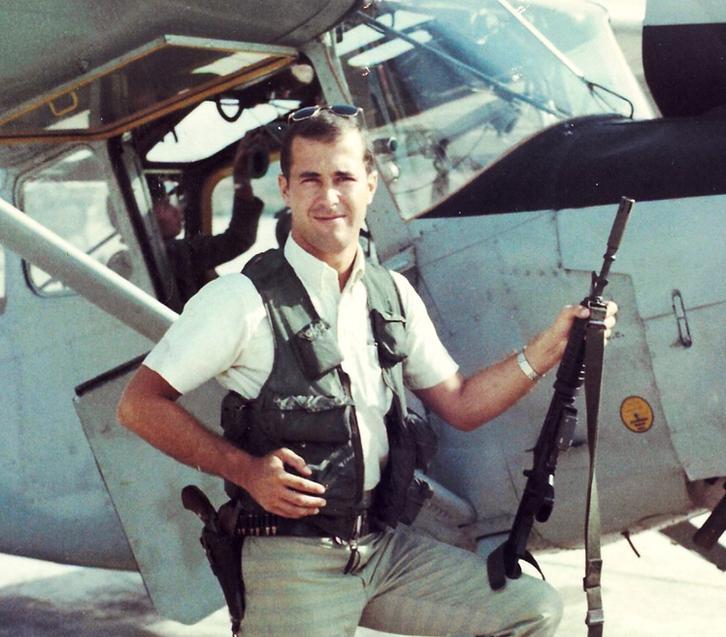

The Raven’s preferred aircraft of choice was the O-1 Bird Dog. It was a versatile, light aircraft that required little maintenance, but it had some limitations to its performance such as range and speed. Nevertheless, the O-1 performed well enough and was cost-effective compared to larger, bulkier airframes. It was also durable and easy to fix. The O-1s carried rocket launchers on under-wing pylons for deploying target markers as well as VHF and UHF radio sets [source].

Because a number of earlier O-1s did not have any UHF capabilities, the 606th Air Commando Squadron donated a slightly larger U-17B Sky Wagon. Besides being FACs, the Ravens also dropped CIA PSYOP material over areas selected by the local Lao ground commanders. Project 404 staff were intimately involved in developing the PSYOP material, which was then distributed by the 606th [source].

5.2 Recruiting a Raven:

By virtue of the project’s secret nature, filling the role of Raven FACs was a difficult task. The experience of Capt Darrel D. Whitcomb, otherwise known as Raven 25, illustrates the covert, yet legendary status the Raven program held among USAF aviators in Vietnam. According to Whitcomb, an OV-10 Bronco pilot with the 23d TASS, he heard whispers about “special programs” across the border in Laos. Whitcomb recounts:

According to Lt. Steve Wilson (Raven 27), the process was far more direct. Wilson, another OV-10 pilot, came to find out about the Ravens through a combination of rumours and a job posting:

Going from an OV-10 to an O-1 was a challenge in it itself. The O-1 was a “tail-dragger”, meaning that on landing, the aircraft’s tail wheel would drag along the strip [source]. The plane would be at an incline at take-off and landing, which could potentially disorientate a pilot unfamiliar with the configuration. If the aircraft brakes were incorrectly applied by the pilot, a nose-over incident may occur, where the tail of the aircraft flips over and places the aircraft on its back.

5.3 Onboard Equipment:

The Ravens often carried AK-47s with folding stocks and shortened barrels. Extra magazines were carried in the cockpit. Oftentimes the Ravens would carry Swedish K submachine guns or CAR-15s. The USAF standard issue sidearm was the .38 Combat Master pistol. An M79 grenade launcher for smoke grenades was sometimes included in the kit, though this was less common. Raven O-1 aircraft were equipped with 2.75-inch marking rockets attached to underwing pylons, negating the need for the space-consuming M79. The Ravens were given grease pencils, essentially early versions or erasable markers, in order to write operation-specific notes on the cockpit windows. A standard-issue USAF aviator helmet was also given to the Ravens as well as a survival vest [source].

5.4 Select Aircraft of the Ravens:

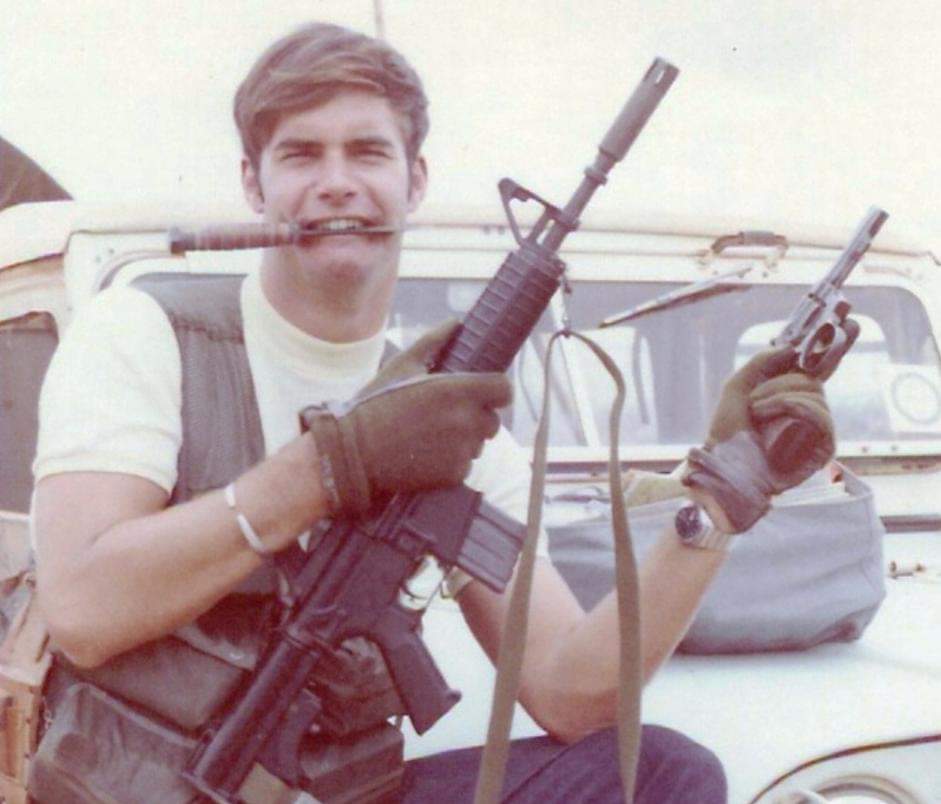

As mentioned previously, the Ravens preferred the O-1 Bird Dog over all other aircraft. However, the O-1 was not the only aircraft the Ravens used. This is a widespread misconception about the Ravens. Pictured below is an O-1 Bird Dog, often associated as a Raven aircraft. This particular aircraft was never used by the Ravens. This picture was taken near Saigon in 1967, not Laos. Raven O-1s did not have any USAF markings and were painted grey with a red stripe above the wings [source].

The O-1s used by the Ravens had a single piece of armour beneath the pilots’ seat, limiting the rate of climb of an already slow aircraft. On top of this, the O-1 had visibility above the pilot seat, allowing the pilot to observe aircraft on bombing runs above the aircraft. The O-1 was not the exclusive aircraft of the Ravens. Swiss manufacturer Pilatus also provided the PC-6 Porter for FAC use [source].

The PC-6 was developed for use in Switzerland’s alpine geography and was a wildly successful STOL aircraft. It had a larger interior space and could be used to transport Hmong insurgents as well as the FAC. The Ravens also used the Helio U-10 Super Courier, the Cessna U-17 and U-6 Beaver as well as the T-28 Trojan [source].

6. End of an Era:

The US government first acknowledged the presence of US military personnel in Laos in October of 1970 [source]. According to Raven 25 (Capt Whitcomb), the project came to an end on February 22, 1973 [source]. The Paris Peace Accords had been signed in January of that year, ending the US involvement in Southeast Asia.

As the US advisory forces left the country, the Pathet Lao made steady gains and by 1975, had captured the capital of Vientiane. The King of Laos abdicated the throne in December of 1975 [source]. The Lao People’s Democratic Republic was proclaimed and the leader of the Pathet Lao, Prince Souphanouvong, was inaugurated as its first president [source].

Despite the loss of Laos to the communists, the Ravens soon became a semi-mythological air unit. They had endured untold hardships and did so without the benefit of publicity. Capt Whitcomb summarizes the mentality of a soldier at war:

7. Summation of Key Findings:

- The United States did not unilaterally violate the provisions of the 1962 Declaration on the Neutrality of Laos. The North Vietnamese, Chinese and Soviets all had military units, advisory and training missions in the country.

- The Secret War in Laos resulted from the unwillingness of the North Vietnamese to disengage from Laos in 1962.

- The Ho Chi Minh Trail was developed as a means of securing strategic depth by the Viet Cong. Laos was used as the platform for this supply chain.

- North Vietnamese support for the Pathet Lao was incidentally based on its need for the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

- The use of air power against insurgents is rendered useless by the ability of the insurgents to disperse. The mountainous geography of Laos made artillery and line-of-sight techniques for target acquisition nearly pointless.

- The Raven project was born out of a sense of elitism by the USAF officer corp and the lack of trust in non-commissioned officers to handle FAC aircraft.

- The CIA’s airline, Air America, played a vital sports role in the Raven, 404 and Palace Dog projects as well as earlier programs such as Water Pump, White Star and Hotfoot.

- The US mission in Laos changed year to year and was reflected in the ever-changing nature of the programs and projects.