Operation Gladio was an Italian paramilitary organisation and it was part of an international network, the so-called “Stay Behind”. The CIA created this organisation because it feared the invasion of Western Europe from the Soviet communist block.

History of Operation Gladio

After the creation of NATO in 1949, the US and the other members, driven by the fear of a communist invasion, established the Clandestine Planning Committee (CPC) at the Supreme Headquarters of Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE).

The idea behind the CPC was to coordinate the various military and paramilitary organisations of the members of NATO and other partners such as Austria and Switzerland. The first three nations which adhered to the CPC were France, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The 1950s

Many Italian documents identified the creation of Gladio on the 26th of November 1956. As a matter of fact, the idea of Stay Behind and Gladio was conceived in October 1951.

On the 8th of October 1951, General Umberto Broccoli, the then head of the Military Information Service (SIFAR – Servizio Informazioni Forze Armate) sent a memo to general Efisio Marras, the then Chief of the Italian Defence Staff. This message contained orders regarding the creation of a network able to provide intelligence and sabotage communist facilities within the Italian territories. This network would have been on standby until a potential communist invasion from Soviet factions.

The Italian clandestine network was expected to be ready by the end of 1953, after completing various courses and training in the UK.

Even though Italy and the CIA had not implemented the agreement yet, the SIFAR started building a military base in Capo Marrargiu, in Sardinia. In order to justify various money transfers from the US and to overcome bureaucratic issues, the SIFAR established a limited liability company called Torre Marina. Leading the company there were General Musco, the then head of SIFAR, Colonel Santini, head of the Operative Information and Situation Service Air Force (SIOS – Servizio Informazioni Operative e Situazione), and Colonel Fettarappa, in charge of the counterintelligence unit of the SIFAR.

On the one hand, Italy would have provided field support, soldiers, and military bases. On the other hand, the United States had to provide military equipment and money.

From the 9th of October to the 15th of November 1957, six members of SAD went to the US for a training course with Robert Palmer, the CIA agent responsible for Gladio in Italy.

The 1960s

As the years go by, other countries, such as Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxemburg, joined Operation Gladio. Italy officially adhered in 1964, however bilateral agreements between SIFAR and CIA were already operating.

Italy was a key nation within this organisation due to its location within Europe and its proximity to the Soviet Union.

In 1965, the then Defence Minister Tremelloni decided to dismantle the SIFAR. It was accused of illegally collecting dossiers about the Italian ruling class on behalf of the CIA. Consequently, the then Italian Secret Services (SID – Servizio Informazioni Difesa) took charge of Gladio.

The Discovery of Operation Gladio

Gladio activities continued in the 1970s and 1980s, but in 1984, Vincenzo Vinciguerra made allegations regarding a clandestine network. Vinciguerra was a member of the fascist organisation New Order. During the process of the Peteano massacre, he stated that in Italy there was a secret organisation able to counter a Soviet invasion on Italian territories.

Only on the 24th of October 1990, did Italian Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti admit the existence of Operation Gladio in front of the Senate.

The Italian Government formally disbanded Organisation on the 27th of November 1990.

Operation Gladio in Europe

These clandestine networks spread all over Europe had the same functions, but they had different names:

- In Austria there was “OWSGV”, which stands for “Österreichischer Wander-, Sport- und Geselligkeitsverein“. It means „Austrian Association of Hiking, Sports and Society“.

- In Belgium, “S.D.R.A VIII”, which stands for “Service de Documentation, de Renseignments et d’Action VIII”. It means “Documentation, Intelligence, and Action Services”.

- In Denmark, “Absalon”, named after a Danish archbishop.

- In Finland, it remains unknown.

- In France, “Plan Bleu”.

- In Germany, “TD BJD”, which stands for “Technisher Dienst Bund Deutscher Jugend”. It means “Technical Services of the League of German Youth”.

- In Greece, “LOK”, which stands for “Lochoi Oreinōn Katadromōn”, which means “Mountain Raiding Companies”.

- In Luxemburg, “Stay Behind”.

- In the Netherlands, “I&O”, which stands for “Operatiën & Inlichtingen” and it means “Operation & Intelligence”.

- In Norway, “ROC”, which stands for “Rocambole”

- In Portugal, “Aginter Press”, also known as “Ordem Central e Tradição”, which means “Central Order and Tradition”.

- In Spain, “Red Quantum”.

- In Sweden, “AGAG”, which stands for “Aktionsgruppen Arla Gryning” and it means “Action Group Arla Gryning”.

- In Switzerland, “P26”, which stands for “Projekt-26”.

- In Turkey, “Kontrgerilla”, which means Counter-Guerrilla.

- In the UK, “Auxiliary Units”.

Structure of Operation Gladio

In 1956, the office SAD (Studi Speciali e Addestramento del Personale, which means Special Studies and Personnel Training) was created within the SIFAR. It had the task of managing and training the new Gladio’s recruits.

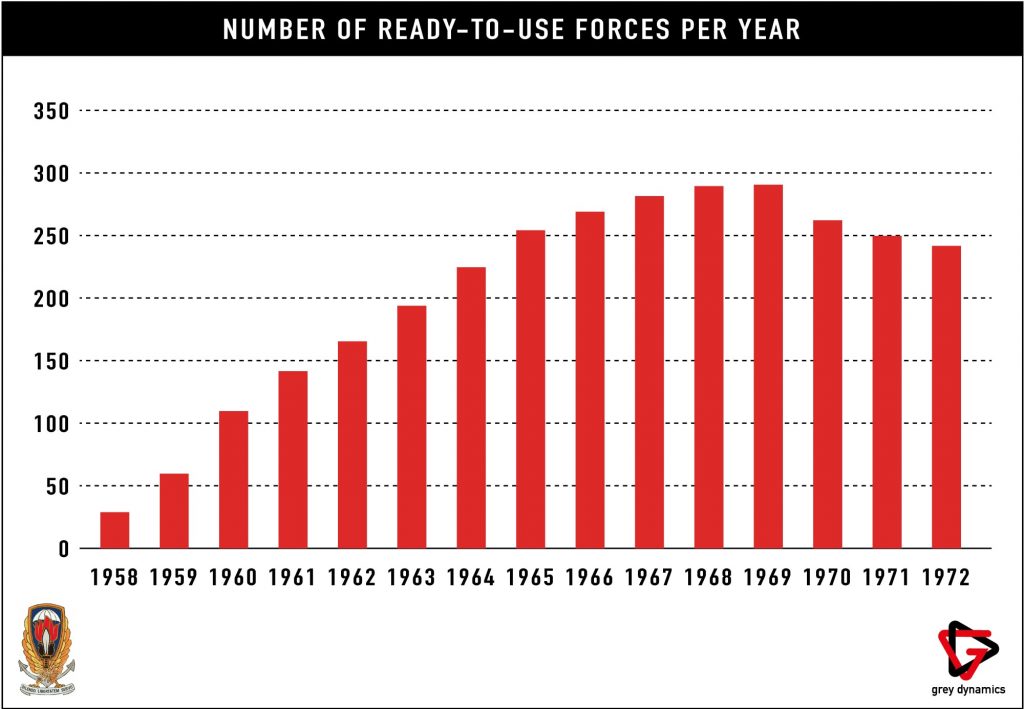

The SAD office enlisted the first soldiers in 1958.

Operation Gladio was based on two different structures. The first one was the most secret and it consisted of unexpected figures that had to work for a long time on occupied territories. The second one comprised a guerrilla unit, ready to be used in case of invasion.

The second structure comprised 40 groups:

- Six groups focused on data and intelligence.

- Six groups specialised in evasion and escape.

- Six groups focused on propaganda.

- 10 groups specialised in sabotage.

- 12 groups specialised in guerrilla.

The SAD then established five more groups in particular regions.

These five ready-to-use guerrillas were:

- “Stella Alpina” in Friuli-Venezia Giulia.

- “Stella Marina” in the area of Trieste.

- “Rododendro” in Trentino Alto Adige.

- “Azalea” in Veneto.

- “Ginestra” in Lombardy, in the lakes area.

In 1991, the Italian Council published a list containing 622 names of gladiators (Gladio’s fighters), of which 45 deceased. According to this data, 408 people were part of the “most secret network” and 214 of the “ready-to-use units”. The 622 gladiators were either “ready-to-use forces”, which means they were ready to be deployed when needed, or “in reserve”, which means they were enlisted but then they were not chosen for various reasons.

Gladio kept recruiting new people until 1972 when the SID dismantled the Nasco (NDR – nascondigli di armi), Gladio’s hiding places for weapons.

Between 1974 and 1976, the SID planned the restructuring of Organisation Gladio. It wanted to integrate some of the groups and establish three more groups. The planned number of gladiators was supposed to be around 2874, but it never materialised. The average number of gladiators remained around 250.

Responsibilities

Other than being ready for a communist invasion, Gladio had various tasks, such as:

- to help prominent people and military personnel to leave occupied areas.

- to be able to maintain the fight against the Soviets, until the US would have reached the area and joined the fight themselves.

Gladio was not only a defence tool but it also had the task to implement the so-called Demagnetise plan. The CIA elaborated this plan. It consisted of a series of paramilitary, political, and psychological operations aimed to decrease the presence of the communist party in both Italy and France.

On the other hand, in times of peace, Gladio was responsible for:

- Acquiring and preserving the military equipment and means of transportation received by the United States.

- Organising training with other Allied forces.

- Recruiting future gladiators and individuals specialised in a specific field of interest.

- Training the recruits.

Organisation Gladio: The Training

Outside of Capo Marrargiu military base, there was the emblem of Organisation Gladio, which was a sword. There was also the motto “Silendo Libertatem Servo”, which means “Silently, I protect freedom”.

Within the military base there were:

- Two airstrips for aircraft and one for choppers.

- Areas dedicated to the courses on how to use and handle explosives.

- Classrooms.

- Diving equipment for frogmen’s training.

- Shooting ranges.

- A small harbour.

- Underground bunkers.

Within Capo Marrargiu military base there were the “internal” (“interni” in Italian) soldiers, who were part of the 7th Division of the Military Services. They had the task of training the “externals” (“esterni” in Italian), which were the gladiators.

Units of trained special assault engineers, part of the CAG (Centro Addestramento Guastatori), a training body for secret services’ operatives were also using Capo Marrargiu base.

The SIFAR was responsible for the recruitment. After the SIFAR flagged an individual, it had to conduct more investigations. The SIFAR recruited men, women, civilians, and servicemen, but these could not have any kind of links with both far-right and far-left parties or individuals.

All the gladiators knew each other only by names, not last names. During the training, they had to remain incognito.

All the gladiators had to attend courses from 08.00 to 12.30 am and after a short break, they had to continue until 01.00 am in the morning. They also had to undergo intense physical training. Moreover, the training focused on sabotage and low-intensity war techniques, the clandestine introduction of Allied special units on the occupied territory, and how to remove from the occupied areas prominent people, such as politicians, spies, or scientists.

Equipment

In accordance with the agreements between the US and Italy, the CIA was responsible for providing the military equipment buried in sensitive areas, the so-called Nasco. From 1963, around 139 Nasco were established and hidden, mostly in the North of Italy. Among the equipment sent by the US there were:

- 12 57mm pivot guns.

- 24 60mm mortars.

- 24 rifles with telescopic sight.

- 106 firearms packs, containing a Sten gun, two pistols, and six hand grenades.

- 120 30mm carbines.

- 198 blast packs in metal containers.

- 364 phosphorus bombs.

The US also provided an aircraft, the Dakota C-47, named “Argo-16”, for transport operations.

This equipment was either from the US itself or was from American military deposits in Germany. The collection base was in Livorno, at Camp Derby, which was also the American logistics centre for Gladio.

On the 24th of February 1972, the Carabinieri of Aurisina found one of the Gladio’s Nasco, containing weapons, dynamite, and other firearms.

Fearing that fascist groups could have found other Nasco, the SID decided to dismantle all of them, but it managed to recover only 127 out of 139.

While the SID was getting rid of the various Nasco, on the 31st of May 1972, an explosion killed three Carabinieri in Peteano. The explosive that was used in that massacre was the same one found in Aurisina.

Past Missions of Operation Gladio

Officially, Organisation Gladio never took part in any kind of mission. However, many suspect that this is not true.

Enrico Mattei

Enrico Mattei, chairman of ENI, the Italian National Fuel Trust, between 1953 and 1962, died in 1962 in a plane crash. In 1995, the judges Roberti and Dini and Casson, the assistant district attorney in Venice, were the first to suggest the involvement of Gladio in Mattei’s death.

Two were the reasons behind this hypothesis. The first suspicion fell on one of Mattei’s bodyguards, Giulio Paver, which was also a member of Gladio. Secondly, Captain Grillo, the one in charge to check the aeroplane before the take-off, was a gladiator as well. After a few months after Mattei’s flight, Paver left his job at ENI.

The death of Mattei occurred in such a specific period of time that the hypothesis of homicide had to be taken into account. With his success in the energy field, he antagonised the Seven Sisters, which were the then giants in the gas and oil field. At the same time, he was supporting the import of Russian oil in Italy, which was against the US and consequently the CIA.

Aldo Moro

Aldo Moro was one of the founders of Christian Democracy, a Christian democratic political party in Italy. The Red Brigades (BR), an Italian far-left armed organisation abducted him on the 16th of March 1978 and then killed him on the 9th of May of the same year.

Some investigations proved that Gladio knew about Moro’s abduction 14 days before and that the bullets shot by the BR were the same found in some Nasco.

Secondly, on the morning of the kidnapping, Colonel Camillo Guglielmi, a Gladio trainer at Capo Marrargiu, was accidentally on the crime scene.

Finally, the same printer the BR used to do propaganda against Moro was the same one used in a Gladio office specialised in training the gladiators.

Moro at the time of his abduction was involved in a process against the BR.

Ilaria Alpi and Miran Hrovatin

Alpi and Hrovatin were in Somalia to cover Operation Restore Hope, but also to investigate the illegal trade of weapons between Somali warlords and the Italian government.

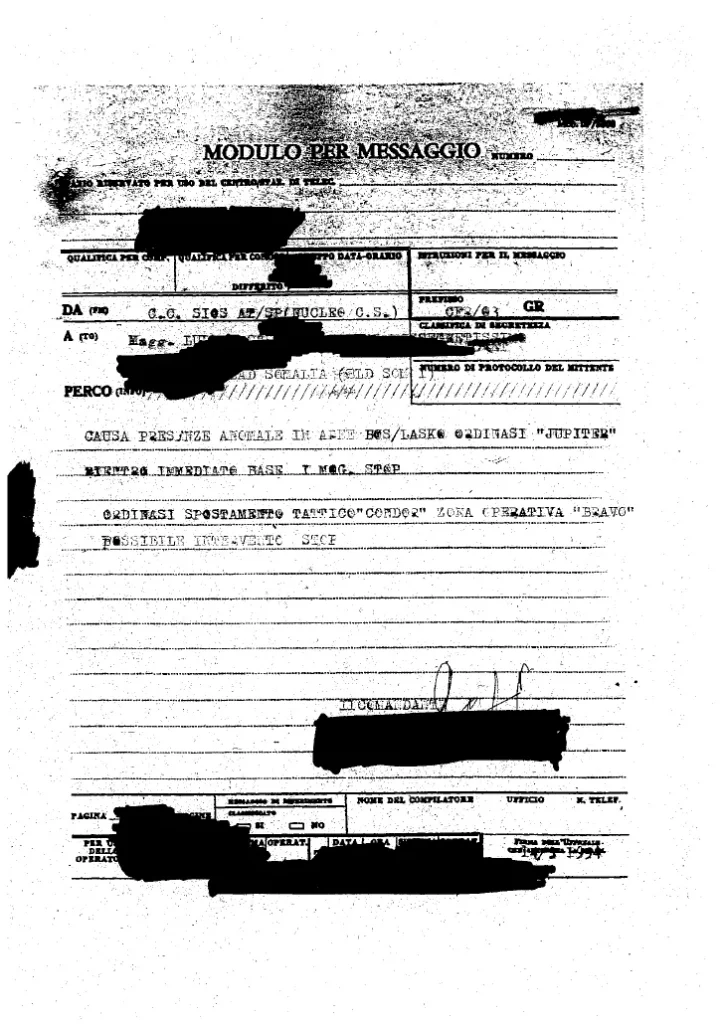

The same day that Alpi and Hrovatin arrived in Bosaso to continue their investigations, the La Spezia SIOS, an Italian security service, sent a message stating: “Due to the presence of anomalies in Bosaso, Jupiter has to immediately come back to the base I Moq. Condor has to join Bravo for a possible intervention”.

The two agents Jupiter and Condor were then identified as Giuseppe Cammisa and Marco Mandolini, and one of Gladio’s units hired them.

Another evidence that links Gladio to this accident is the close friendship between Alpi and Sergeant Vincenzo Li Causi, an Italian secret agent. It is highly likely that Li Causi provided information to Alpi and Hrovatin regarding the Italian illegal trade. Li Causi was found dead in November 1993. The circumstances of his death are still unclear. Alpi and Hrovatin were killed soon after, on the 20th of March 1994.

Nonetheless, there is clear evidence of Gladio’s involvement, its role in these accidents is not official.