The history of warfare and politics is littered with prime examples of the value of intelligence and the risks that come with ignoring its utility. The practice of this art extends well into antiquity and its prevalence across the centuries is a testimony to its significance and consequence. This series is designed to illustrate that value and to identify pivotal moments where intelligence practitioners changed the course of history. In the first part of this series, we will examine how a system of intelligence can completely fail and what lessons modern day intelligence practitioners can glean from the terrible episode of 7 December 1941.

1.0 America on the Defensive

On a muggy December morning in 1941, Pharmacist’s Mate Sterling Cale was finishing up a tiring night of work at the naval dispensary on Ford Island. At 7:55 AM, the Hawaiian sun blazed and by every indication, it was a peaceful, regular morning for the youthful “farm boy from Illinois.” His world, and indeed the world at large, would be shattered in mere moments. As he left the dispensary, he looked up and stared at a swarm of planes flying over Battleship Row. He thought to himself:

“Why are planes over at Battleship Row? That’s a lot of activity for Sunday“.

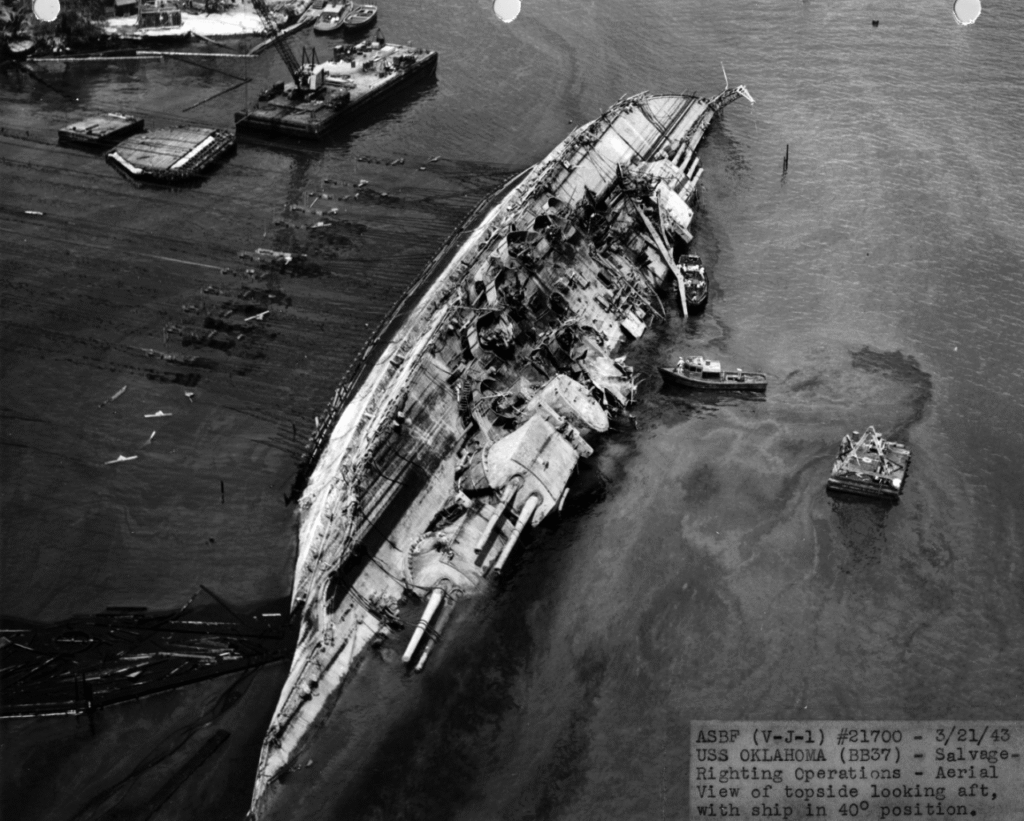

His confusion soon melted into terror as he noticed the red circles on the underside wings of the aircraft. Running back into the building, he broke into the naval armory and began distributing rifles. He was later reprimanded for entering the armory during “peacetime” but was quietly awarded a pack of cigarettes the following day. He bolted outside with a group of men and began running in the direction of the USS Oklahoma. A horrific scene greeted them as the massive ship began to capsize. [source]

Across the island on the Oklahoma itself, Gunner’s Mate Paul Aschbrenner, was performing his regular duties on the deck of the Nevada Class Battleship when a voice belted out on the loudspeaker “man your battle stations, this is no drill.”

Just as he began to make his way down to the powder deck, a torpedo slammed into the hull. The lights gave out and Aschbrenner noticed the ship beginning to list heavily. Aschbrenner just barely escaped the capsizing wreck from one of the main turrets. [source]

2.0 Success of Japanese Intelligence

When the last aircraft departed the harbor, the carnage left in the wake of the Imperial Japanese Air Force could be fairly categorized as devastating. With nine battleships either sunk or damaged, three cruisers and four destroyers similarly inoperable and five auxiliary ships capsized, sunk or beached, the US Pacific Fleet was broken. 188 aircraft were incinerated and a further 159 were wholly damaged. In total, 2,403 US service members lost their lives. [source]

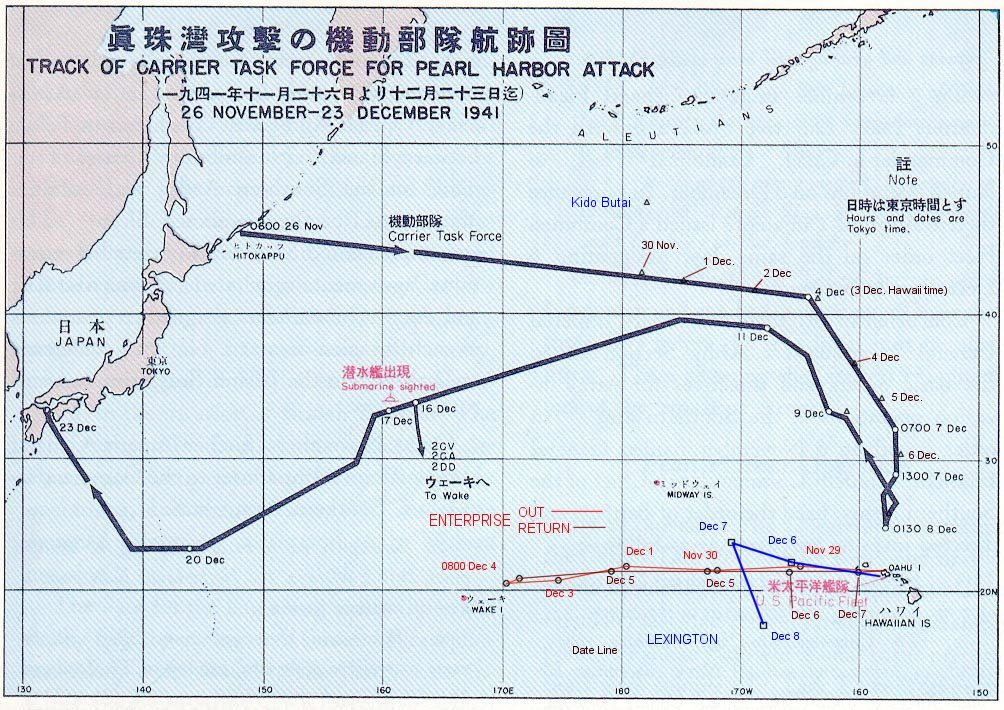

The fact that a strike group of seven IJN carriers could cross the length of the Pacific Ocean and avoid total detection was already an intelligence success in its own right. The Japanese struck a decisive blow to American naval power in the Pacific. The sheer loss of life combined with the destruction of multiple major surface combat warships appeared to be final and conclusory.

More specifically, it was a coup de’gras of operational security and counterintelligence efforts by the Japanese. So how exactly did the Japanese manage to keep this entire operation under wraps?

2.1 Anatomy of Japan’s Intelligence Efforts

Since at least 1934, the Japanese government maintained a highly active intelligence network in the continental United States. The US Navy’s COMINT unit uncovered at least two individuals who were passing the Japanese bits and pieces of information since early 1934. One of these spies, Harry Thompson, was a lowly clerk in the US Naval Department, hardly a Manchurian Candidate type figure.

Thompson was a former Navy administrative specialist and was able to don his old uniform to surreptitiously gain access to naval facilities in San Diego. There, Thompson would jot down notes about naval capabilities and new weapons systems and pass them along to his recruiter and handler, Lt. Commander Toshio Miyazaki, an Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) intelligence officer who was ostensibly in the United States on a foreign language exchange program. [source]

The other spy, John Semer Fransworth, was in a considerably more senior position than Thompson. Fransworth was a former Lt. Commander, and was able to use his position of trust to scalp sensitive documents off his former military colleagues and pass them onto the Japanese. [source]

2.2 Japanese HUMINT

Both Fransworth and Thompson were essentially broke. Thompson himself was enticed with $500 monthly payments (approximately $9,375 in today’s money). It is unknown how much Fransworth was paid, but his financial troubles were reportedly extensive. The intelligence provided by Fransworth was also of significantly higher quality than Thompson’s. According to the Association of Former Intelligence Officers, Fransworth “had compromised the gunnery capabilities of every US ship.” [source, source]

Japanese HUMINT on the island of Oahu was even more comprehensive. For example, in March of 1941, the IJN stationed Lt. Takeo Yoshikawa at the Japanese Consulate in Honolulu in order to reconnoiter the island using the cover of a diplomatic mission. It is often said that Yoshikawa never committed a single piece of information to paper, knowing that it may lead to his arrest if discovered [source]. In truth, this may be a piece of self-serving romanticization, egged on by Yoshikawa himself. Regardless, his efforts were extensive.

A former pilot, Yoshikawa was based in an apartment overlooking Pearl Harbor. Not satisfied with his ideal perch above the harbor, Yoshikawa rented planes, small boats, cars and traversed every last inch of the base perimeter. At one point, Yoshikawa even swam around the island. He communicated vital details about the general schedule of military activity at Pearl Harbor and base layout [source].

2.3 German Intelligence Cooperation

Yoshikawa collaborated with Nazi Germany Abwehr agents based in Honolulu, a pair of brothers, Otto and Friedel Kuehn. The Kuehn brothers provided the German High Command with intelligence reports about Pearl Harbor in their own right, but with Yoshikawa, the body of information only grew and grew. Yoshikawa was so successful in evading detection that, despite consistent efforts by the FBI, the Bureau simply could not make anything stick to the man.

The Germans sent an agent known as Dusko Popov to establish a spy ring in Honolulu. As an erstwhile double agent for the British, British Intelligence warned the FBI of Popov’s arrival. Hoover generally considered his British counterparts in an adversarial light, and did not exactly think Popov warranted further inquiry.

Even more damning, there is credible evidence that Hoover was in possession of four separate microdot manuscripts supplied to the FBI by Popov himself. The information contained on these microscopic specimens indicated a strong German interest in Pearl Harbor’s layout and defences, as well as at least 11 separate sensitive military sites across the island [source]. In the words of James M. Olson, author of ‘To Catch A Spy: The Art of Counterintelligence’:

“Someone should have been smart enough to ask why the Germans seemed so interested in Pearl Harbor.”

Clearly, no one, not even Hoover, had that foresight.

For his part, Otto Kuehn had a unique system of several signals that would communicate valuable information to the Japanese consulate. If his handlers saw a light in a specific window of his Lanikai beach house between 9-10 PM, the American carriers had departed the base.

If they saw a linen sheet on the clothes line between 10-11 AM, the entire battle fleet had departed the harbor. He had even worked out a complicated system of signals that Japanese midget submarines could reference when approaching the island. Kuehn provided detailed intelligence reports using this system to the Japanese at least 5 days prior to the attack. [source, source]

2.4 Japanese SIGINT Efforts

In another era, Japan and Germany were enemies. During the First World War, Japan stormed German islands in Micronesia and Germany’s colonial possessions near Tsingtao. In the aftermath of the Treaty of Versailles, Japan was awarded German islands such as Kwajalein Island in the Marshall Atoll. Approximately 4,134 km from Hawaii, the Japanese used a radio direction finding station on the island to track US patrols, identifying where the US aircraft left gaping holes in their coverage. [source]

3.0 Failure of American Intelligence

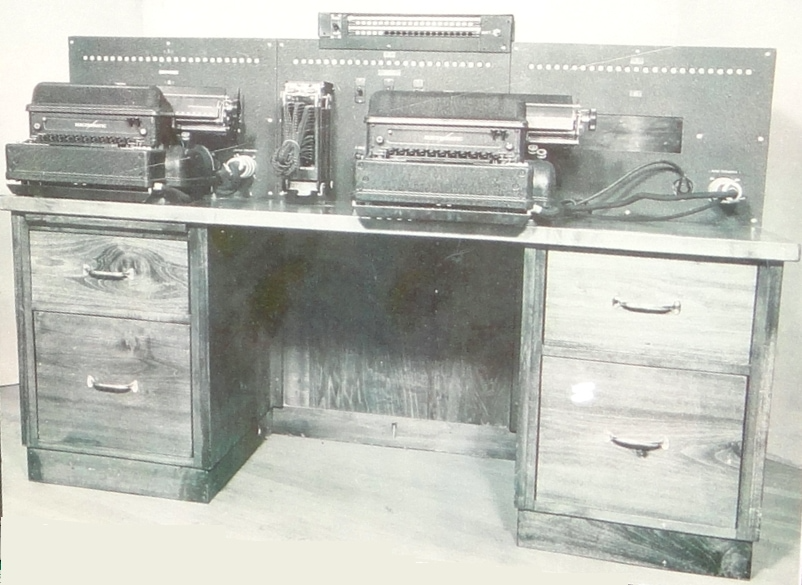

Despite having a nascent COMINT system in the form of MAGIC PURPLE, US codebreakers were unable to decipher any meaningful encrypted communications that would forewarn a Japanese attack. PURPLE communications only carried messages from the Japanese Foreign Office. The IJN used an entirely separate encryption machine. At best, the SIS intercepted a dispatch informing the Japanese Embassy in Washington that diplomatic relations were to be broken off at 1 PM on 7 December. [source]

Nevertheless, that alone was a clear indication of impending conflict. What’s more, Lt. Gen. Walter Short, joint commander at Pearl Harbor, was repeatedly warned that rising tensions with Japan could lead to all out war. He received multiple dispatches on 16 October, 24 November, and 27 November that explicitly stated “this dispatch is to be considered a war warning,” and that “negotiations have ceased.” [source]

To worsen matters even further, the Navy and FBI ran into jurisdictional ran into a bout of jurisdictional jostling over wiretapping the Japanese Consulate in Honolulu. Naval intelligence had in fact tapped the phone lines at the consulate building right up until 2 December of 1941 [source]. At the heart of this was a legal concern over intercepting telephone communications as opposed to diplomatic cables. Moreover, the Navy reportedly held concern that the taps might be discovered, triggering an international incident. The FBI flexed its counterintelligence mandate and continued the taps, intercepting at least one phone call mere days before the attack indicating that documents were being burned in the consulate. Later congressional inquiries found that this intelligence was not communicated to the Navy in a timely and decisive fashion [source]. This wiretap issue perfectly encapsulates a systemic flaw in the US intelligence community at the time, namely an absence of clear intelligence authority and cogently understood prerogatives.

3.1 Unheeded Warnings

Erroneously believing that the main threat to US military assets in Hawaii came from Japanese nationals engaging in sabotage operations, Short ordered the Army’s aircraft to be clustered together on Ford Island and Wheeler Field so that they would be better guarded. This led to a wholesale disaster. When Japanese bombs fell on Ford Island, flames leapt from aircraft to aircraft, leading to a chain reaction of destruction as exploded fuel tanks spewed burning propellant on the tarmac. [source]

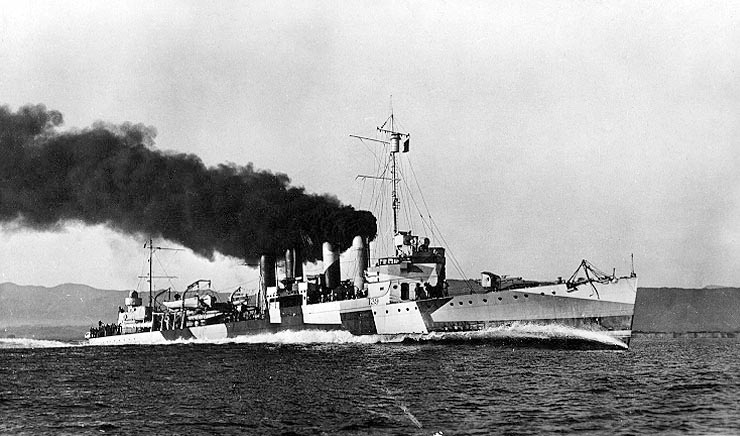

Even worse than these major lapses of judgment, the morning of the attack itself carried blaring sirens that fell on deaf ears. The minesweeper USS Condor observed what later was identified as a Japanese midget submarine operating off the waters of Hawaii, and some hours later, the same sub engaged with the destroyer USS Ward. Depth charges were dropped and the sub was actively fired upon by the Ward’s 4 in (102mm) gun battery. [source]

Admiral Husband Kimmel was made aware of these engagements but sat on this information to await further confirmation. Lt. Gen. Short for his part, in keeping with the theme of poor decision making, instructed radar units to operate their systems only between the hours of 4:00 AM and 7:00 AM.

By mere chance, U.S. Army Pvt. George Elliott elected to stay over on his radar system and run practice tests with the device. He observed a large blur on the screen, indicating a massive flight of aircraft approaching the island. He elevated this information to his superiors, who told him to ignore the radar return. Pearl Harbor was expecting a contingent of B-17 bombers that morning, and this was probably them. [source]

4.0 Dissecting the Failures

From these series of events, we get a sad picture of incompetence and missed opportunities. Let’s examine the most pressing and glaring ones as they relate to America’s wartime footing in 1941.

- The process of decoding PURPLE intercepts was slow and tedious. This often meant that by the time the information was decrypted, the information was non-actionable. [source]

- Prior to 1942, the Military Intelligence Division was understaffed and was considered a “dumping ground for incompetents” by the wider military community. [source]

- Very few individuals in Washington had access to MAGIC PURPLE decryptions, meaning that the number of people who could handle the intelligence was limited to whoever was available at any given moment. [source]

- In that sense, too few people with decision making power had possession of critical intelligence. The ones who had immediate access were unqualified and untrained to handle the information or were unable to make decisions on the basis of the intelligence.

- The US Army did not invest in HUMINT networks in east Asia. Further, intelligence efforts were dedicated to countering “subversion” in 1941 and not towards identifying Japanese military activity [source].

5.0 Mentality of Denial

No matter how we choose to dissect the systemic failures which led up to the attack, there is one widely accepted observation. Every member of the officer corps, political leadership and intelligence officials tasked with securing America’s peacetime defenses simply failed to communicate with one another and do the basic minimum required by their high offices.

For example, early warning signs such as the presence of a Japanese submarine off of Hawaii and the active radar monitoring of the incoming Japanese aircraft were totally ignored.

Ignoring the obvious and present indicators of incoming Japanese military assets was a symptom of believing the US was in a peacetime setting. Indeed, the wanton dismissal of the clear and present evidence of danger would be the only appropriate mentality adoptable by a military that fundamentally believed it was not staring down the gunbarrel of war. The belief that war was not inevitable, avoidable even, was the most proximate cause of the intelligence failure which made Pearl Harbor inevitable.

This symptom could have been alleviated if Kimmel and Husband adequately heeded warnings and placed the forces under their command on a wartime footing. Alas, both Kimmel and Husband suffered from the same ambulatory atmosphere of denial that emanated directly from Washington. In other words, the mentality of obstinacy, refusal to believe in what was clearly metastasizing in front of one’s eyes, allowed otherwise capable military and political professionals to bury their heads in the sands.

6.0 Conclusion

The failures of intelligence at Pearl Harbor resulted in sweeping reforms to the American intelligence apparatus. Between numerous military and congressional inquiries, including the Robert’s Commission, effectively placed the blame at the feet of Kimmel and Short. The United States Congressional Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack issued several recommendations. A number of these items were later codified into the 1947 National Security Act, giving birth to the modern Pentagon and later the CIA.

The failure of American intelligence at Pearl Harbor was really a function of how successful Japanese intelligence was in operating unabated and undetected. In short, American intelligence failures allowed the Japanese to compound and exponentially leverage their own intelligence successes. On top of this dynamic, the inability of the United States’ political and military leadership to recognize a new situation when one arose contributed heavily to this atmosphere of denial outlined above.