Introduction

The National Intelligence Center in Mexico, known in Spanish as “Centro Nacional de Inteligencia” (CNI), is the institution tasked with preserving the stability of the Mexican State through strategic, tactical and operational intelligence. Former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador created the CNI in 2018 as a replacement to the previous Center of Investigation and National Security (CISEN). The CNI is part of the Secretariat of Safety and Civilian Protection (SSPC), which responds directly to the President. However, the National Congress has the ability to legislate on the CNI as well. With a revised annual budget of some USD $160 million, the current administration under President Claudia Sheinbaum has declared her intentions to strengthen and provide the CNI with more capabilities to coordinate intelligence with the General Prosecutor’s Office, as well as the secretaries of National Defence, Marines, Security and Civilian Protection, and the National Guard.

Intelligence services in Mexico trace their origins to precolonial times, when some Mexican cultures had what would now be considered espionage agents, and the Aztecs utilised traveling merchants known as ‘pochtecas’ to collect information. The Aztects used the knowledge gained by pochtecas in warfare to conquer other populations. Centuries later, since the beginning of the twentieth century, the national intelligence services in Mexico have faced numerous changes and reforms. The current CNI is a result of the numerous improvements and evolutions of intelligence in the country.

1. CNI Principles, Symbols, and Motto

1.1. Symbol

The symbol of CNI is a circular logo with the shape of Mexico in the center and the letter ‘CNI’ on top of it. Below the map is written ‘SSPC MEXICO’, which indicates that the CNI operates within the Secretariat of Safety and Civilian Protection. Lastly, on the upper part of the logo, the full name of the institution ‘Centro Nacional de Inteligencia’ is visible.

1.2. Values of Mexican Intelligence

The CNI does not explicitly state its values. However, the National System of Investigation and Intelligence for Public Safety states principles and values that guide it are: legality, responsibility, professionalism, cooperation, coordination, opportunity, need, precision, efficacy, efficiency, loyalty, proportionality, honesty, and confidentiality. Its stated values guiding intelligence work are patriotism, Mexican humanism, cooperative federalism, respect for dignity, and respect for human rights. All institutions conducting intelligence work are expected to uphold these values, including the CNI. [source]

2. Mexican Intelligence History

2.1. Confidential Department: First Formal Mexican Intelligence

Formal intelligence services in Mexico existed since 1920, when the government created the First Section of the Secretary of Interior. In 1929, the president renamed it the ‘Departamento Confidencial.’ This department had two different types of agents: political information agents and administrative police agents. Based on retrieved data from the time, the functions of the department consisted quite simply in investigating, reporting, and executing orders from the Secretary of the Interior.

The Secretary tasked them with maintaining political control of the country by investigating both allies and enemies, officials, candidates, and all types of political groups. This demonstrates how, in the first institutional origins, intelligence services in Mexico were utilised for internal purposes. Furthermore, intelligence served the government to maintain internal control over its citizens. The name of the Confidential Department lasted until 1934, after which the institution was renamed the ‘Office of Political and Social Information’ and later ‘Department of Political and Social Investigations.’ [source, source, source]

2.2. General Directorate of Political and Social Investigations (DGIPS)

In 1942, intelligence services in Mexico faced yet another name change and restructuring. The president transformed and renamed The Department of Political and Social Investigations to the ‘Directorate of Political and Social Investigations’ (DIPS). The creation of the DIPS brought forward further changes in the national intelligence services in Mexico. For the first time since the formalisation of intelligence, internal regulations for the work of the institution were created. However, the tasks and operations inherited from the previous agencies remained.

Furthermore, the context in which the Directorate was created, in the Second World War, required an intelligence service that had control of foreigners in the country. Years later, in 1967, its name changed to ‘General Directorate of Political and Social Investigations’ (DGIPS). This transformation aimed to study the social and political problems of the country. The DIPS, and later the DGIPS, were still conducting secretive operations. These operations included spying on political opposition, foreigners, and those considered the ‘internal enemy.’ The name of DGIPS remained until the 80s. [source, source]

2.3. Federal Directorate of Security (DFS)

2.3.1. DFS Creation and Rise

Alongside the DIPS, the government created the Federal Directorate of Security (DFS) in 1948. This institution collaborated with the DGIPS in intelligence matters since before its formalisation in 1953. The DFS quickly became the ‘political police’ of the PRI ruling party, despite the longevity of the DGIPS in Mexico. The presidential figure in office completely controlled the DFS, which operated independently of military influence. However, and in contradiction with its purposes, several of the officers and the lead director of the office were all military.

The main objective of this new agency was to ensure national security in the country, protect and inform the president of all political activity, and protect the nation from external threats. According to declassified information on the DFS, its regulations tasked it with overseeing all types of political activity and groups, including: student organisations and unions, political parties, news and communication agencies, the international clergy, journalists, socialist embassies in Mexico, teachers union, among others. [source, source, source]

2.3.2. DFS: Ideology and Crimes

With the rise of socialist ideals during the 60s, and support for the communist revolution in the country and the region, the Mexican Government decided to turn the DFS towards a ‘political police’. This change followed the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959. As a result of this, the Mexican intelligence services conducted gross violations of human rights. DFS Officials surveilled individuals based on ideology and largely left the institution unchecked, even after proving its ties to narcotrafficking. In fact, Aguayo Quezada, a Mexican academic expert in intelligence services stated in his book:

“In the country, very few were interested in what was happening inside the DFS. Governments, on their side, were satisfied with the results that the Federal Security provided them, and did not care too much for the methods they employed. Narcotraffic or extortion were considered a ‘boy’s mischief’ of those that flaunted with pride and arrogance their shining credentials.” [source, source, source]

2.3.3. Late Years of the DFS

With the years, the counterinsurgency and security actions of both intelligence agencies in the country gradually increased unchecked. This, eventually led to the massacre of hundreds on 2 October 1968 against a student movement. In fact declassified documents demonstrate the intense surveillance and repression that the DFS imposed in the student movements. [source, source, source]

The decade of the 70s is considered the most violent and repressive, given the over 20 insurgent and guerrilla-style groups that the DFS and the DGIPS were instructed to terminate and disappear, regardless of the means. The success obtained by the intelligence services in repressing the movements and any insurgency meant that the agencies enjoyed ‘alarming levels of impunity’ for decades, which in turn ended up leading towards the demise of the DFS and DGIPS and their later dismantlement. Additionally to the abuses of power and the links to narcotrafficking, Washington accused the DFS of participating in the disappearance and later assassination of DEA agent Enrique Camarena in 1985 and journalist Miguel Buendía in 1984. This situation further pressured the national government to change its intelligence institutions. [source, source, source, source]

2.4. Center for Investigation and National Security (CISEN)

On 29 November 1985, the DFS was dismantled and, in turn, both the DFS and the DGIPS were merged into one integrated intelligence service called the General Directorate of Investigation and National Security (DISEN). The creation of the DISEN aimed to establish a functional and administrative framework within intelligence work to eliminate practices associated with the scandals associated with the two previous agencies. Its establishment as a transitional agency, paved the way for the more permanent one that came four years later, the Center for Investigation and National Security (CISEN).

The establishment of CISEN, under the Secretary of Interior, followed the creation of the Cabinet for National Security in 1988 and occurred under the Presidential Decree of 13 February 1989. The president of Mexico created the CISEN to “1) Establish and operate an investigations system for the safety of the country; 2) Collect and process the information generated by the system […] interpret them and formulate conclusions that derive from the evaluations; 3) perform studies of political, economical and social nature; and 4) perform surveys of public opinion about national interest topics.”

As a result of continuous dialogue between the congress and intelligence services, the CISEN resulted in an ‘unfocused’ organism from the Secretary of Interior with technical and operational autonomy. The Treasury Secretary revised and approved the annual budget of the CISEN, and subsequently informed the Secretary of Interior. In the late 1990s, the presidency consolidated the CISEN to generate strategic intelligence. This consolitdation followed the creation of the Preventive Federal Police. In 2004, expansions in the Constitution regarding the faculties of the National Congress allowed it to legislate in matters of National Security, which included intelligence. [source, source, source, source]

3. Organisation of CNI

3.1. Place in Government

The CNI is a branch of the Secretariat of Safety and Civilian Protection (SSPC). This Secretariat is part of the cabinet that works directly for the president of the Republic. However, the President is not the only one that regulates this institution, but also the Congress. In addition to its operations, the CNI participates in coordinated actions with the Armed Forces, the National Guard, and the General Attorney’s Office of the Republic to combat organised crime, diminish violence, and prevent foreign actors from operating with impunity in the country. [source]

3.2. CNI Operational Tasks

In 2005, the government created the Law of National Security which, amongt other things, regulates intelligence work, and delimits the specific tasks of the then CISEN (now CNI) as follows:

- Intelligence work to preserve the integrity, stability, and and permanence of the State and the Rule of Law;

- Process the information generated by its operations […] and evaluate in order to safekeep the country;

- Prepare political, economic, and social studies related to threats of National Security;

- Elaborate frameworks for the strategic plan and the National Risks Agenda;

- Propose means to prevent, dissuade, contain and deactivate risks and threats against the territory, the sovereignty, the national institutions, the democratic governability, or the Rule of Law;

- Establish cooperation with other institutions of the Federal Administration […];

- Propose to the council the establishment of systems of international cooperation aiming to identify possible risks and threats;

- Acquire, administer and develop technology specialised for the investigation and diffusion of governmental communications in National Security;

- Operate specialised communications technology;

- Lend technical aid to any of the governmental instances in the council; and

- Other dispositions that it is tasked with.

[source]

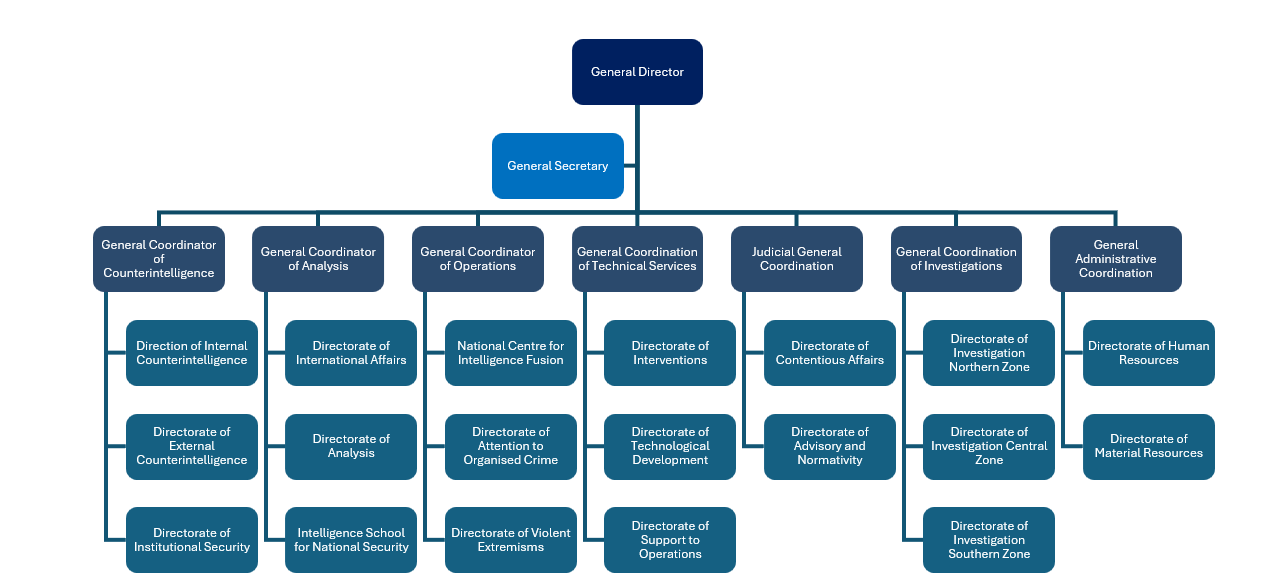

3.3. Organisational Structure

The current structure of the CNI is as follows:

[source]

3.4. General Director

The current director of the CNI is Francisco Almazán Barocio. Previous to his current role as Director, he served as leader of the Investigation Police within the Attorney General’s Office of Mexico City. Additionally, Almazán Barocio previously served as the director of Police and International Affairs, and Interpol Affairs in the Criminal Investigations Office of the Attorney General of Mexico. Within intelligence, the current director used to represent the National Security Commission within the CISEN. [source]

3.5. Personnel Recruitment

The recruitment process for the CNI goes though the general process or recruitment of the Secretary of Safety and Civilian Protection (SSPC). In 2025, the SSPC released a call for investigation and intelligence agents. Those interested in joining, and who met the requirements, must register themselves online, after which the individuals will receive an email with an appointment set no later than 30 working days. The Secretary establishes 17 requirements that all candidates must meet.

- Be a Mexican citizen in full exercise of their civil rights, and with no other nationality

- Have a minimum of a Bachelor’s in specific degrees

- Be between 23 and 35 years old

- Minimum height: 1.50 meters in women and 1.60 meters in men

- Have a record of good conduct, without a sentence for a crime, not owing alimony, not being suspended as a civil servant, amongst other requirements

- For men, having done the National Military Service

- Have good physical and mental health

- Have a Body Mass Index between 18.5 and 34.9 Kg/m2

- Have perfect sight or, show up to the tests with their glasses, if needed

- Do not use psychedelics, or similar drugs

- Not be an alcoholic

- Submit themselves to tests to demonstrate the absence of alcohol or drugs in their system

- Availability to rotate shifts and change their residence within the country

- Pass all the medical, psychological, and physical tests

- Pass the test called ‘Control of Trust’

- Pass the course ‘Initial Formation and Specialisation for an Investigation and Intelligence Agent,’ which lasts 9 months

- Absent any history of dismissal in the National Registry of Personnel of the Public Security.

[source]

4. Scandals and Controversies

Mexican intelligence has experienced numerous controversies throughout its development. Notoriously, the DFS was involved in the assassination of DEA agent Enrique Camarena in 1985 and journalist Miguel Buendía in 1984 as a result of the organisation’s involvement with drug dealers. Furthermore, reports have established that several notorious cartel drug lords, such as Don Neto and Caro Quinetro held official DFS credentials, signed by then director José Antonio Zorrilla. [source]

Most recently, in April 2022, a Canadian investigation laboratory discovered that the Mexican Government utilised Pegasus spyware as early as 2012 against human rights defenders and journalists. In fact, in 2017, Cecilio Pineda, a Mexican journalist, appeared in the list of people requested by the government to be spied on mere weeks before his homicide. This journalist used to report mainly on the ties between politics and narcotraffic in the country. Amnesty International reports that at least 25 Mexican journalists were spied on between 2020 and 2022. However, after the release of these investigations, former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador denied that his government and the CNI had spied on people. [source, source]

5. Conclusion

Intelligence agencies in Mexico have undergone numerous changes throughout the history of the country. The relatively recent creation of CNI is the latest evolution in this process and attempts to distance professional intelligence work from the abuses of previous civilian services. Despite efforts to improve the effectiveness of the CNI and overall intelligence, the ongoing security crisis of the country poses significant challenges. The spread of organised crime, violence, and homicides raise questions about the effectiveness of these institutions. Meanwhile, publicly available information gives few clues as to how CNI is addressing modern challenges to intelligence agencies worldwide, such as cyberespionage, the use of AI, Ubiquitous Technical Surveillance, and OSINT.