1.0 Introduction

China’s Intelligence Community (CIC) is a global powerhouse of clandestine operations. Its long arms are puppeteers behind civilian, political and military assets. Its eyes see far into cyber, corporate and defense sectors. It is an intelligence ecosystem as vast and complex as the Imperial Chinese bureaucracy of old.

The CIC boasts a comprehensive approach to serving both foreign, and domestic Chinese state interests. However, CIC activities go far beyond the scope of what are often popularly thought of as covert operations. Every day, it coordinates handlers across the world, it commands high-tech monitoring tools in cyber, space and traditional domains. It uses agents, analysts, hackers, and assets; technical, recruited, and domestic. The CIC casts a long shadow. It generates intelligence, influence, and intrigue.

2.0 CIC: 21st Century

This article will focus on the nature, structure, and activities of the current state of China’s Intelligence Community. However, to understand the reality of PRC intelligence today, some historical context is necessary. For the purposes of this report, current Chinese Intelligence will be contextualized through the two most recent phases of reforms that targeted it. 2015 marks the central point of reform that realigned and largely transformed Chinese intelligence both in purpose and form. 2024 reshuffled part of the Chinese military intelligence in a substantial way and thus is worth considering.

2.1 2015 – 2017 Reforms

The 2015–2017 reforms were a foundational moment in the modern evolution of China’s Intelligence Community. These reforms critically reshaped both military and civilian intelligence domains. Central to this wave was the creation of the People’s Liberation Army Strategic Support Force (SSF) on 31 December 2015. This was a newly minted service designed to unify and elevate China’s space, cyber, electronic, and information warfare capabilities under one roof. Former 3PLA and 4PLA—the SIGINT and electronic warfare elements of PLA’s military intelligence, which were previously separate—were unified under the SSF.

2.1.1 CIC: 2015

This military restructuring occurred alongside a sweeping shift in national security law. The 2015 National Security Law formally framed intelligence as part of a “comprehensive national security” concept. This was crucial in reconceptualizing the need and function of intelligence in China’s whole-of-society approach to national security.

Next was the former 2PLA. This was the main military intelligence HUMINT, IMINT and tactical reconnaissance bureau of the PLA. In 2016 under major military reforms, the former General Staff Department was replaced by the Joint Staff Department under the Central Military Commission (CMC). 2PLA became the Intelligence Bureau under the Joint Staff Department. This move enhanced the new Intelligence Bureau with the 2PLA functions and personnel but also further enhanced its profile and capabilities. Further, the 2016 Cybersecurity Law, which tied data sovereignty, network operations, and information systems directly into national security obligations blurred the lines between commercial, civilian, and intelligence sectors.

2.1.2 CIC: 2017

In June 2017 the first publicly disclosed National Intelligence Law codified state intelligence work into statute. This effectively obligated individuals and organizations to support state intelligence activities, operationalizing a “whole-of-state” mandate, and clarifying that intelligence agencies could operate domestically and abroad to safeguard national security.

Concurrently, the reforms dissolved the PLA’s old general department system, strengthened the Central Military Commission’s direct control over intelligence and joint operations, and gave the SSF clearer command lines. This enhanced strategic integration and operational coordination across the PLA. These changes elevated intelligence as a whole-of-government process, institutionalized legal authority for collection and cooperation, and centralised the Party’s grip on policy and practice across the CIC.

[source, source, source, source]

2.2 The 2024 Military Intelligence Reshuffle

In 2024, Beijing’s military intelligence architecture underwent another wave of transformation. Most visibly, on 19 April 19 2024, the People’s Liberation Army formally dissolved the SSF. The PLA redistributed its core space, cyber, and information functions into distinct CMC-subordinate arms. The Military Aerospace Force, the Cyberspace Force, and the newly elevated Information Support Force (ISF) now stand alongside the Joint Logistics Support Force as the four “arms” directly under the CMC. This flattening and specialization of military information, cyber, and space capabilities reflects a doctrinal shift toward highly focused intelligence-enabled combat support and tighter political control over these domains.

Concurrently, civilian legal frameworks that affect the wider intelligence ecosystem were strengthened. In early 2024 the Law on Guarding State Secrets was comprehensively revised and broadened. This move expanded categories of protected information to include new “work secrets” and high-technology data. It further tightened obligations on agencies, enterprises, and individuals to safeguard classified material. Thereby it enlarged the legal toolkit available to state security organs outside the PLA.

At the same time, updated procedural regulations for state security enforcement, including new administrative and criminal procedural provisions applicable to MSS operations authorised mid-2024, enhanced the Ministry of State Security’s extrajudicial powers and ability to act with fewer legal restraints.

Taken together, these 2024 reforms not only refined the People’s Liberation Army’s intelligence-related command structures, but also reinforced the statutory foundations and reach of China’s civilian intelligence and state security organs. In short, Chinese state and military intelligence functions were integrated deeper into China’s legal, bureaucratic, and political structure.

[source, source, source, source]

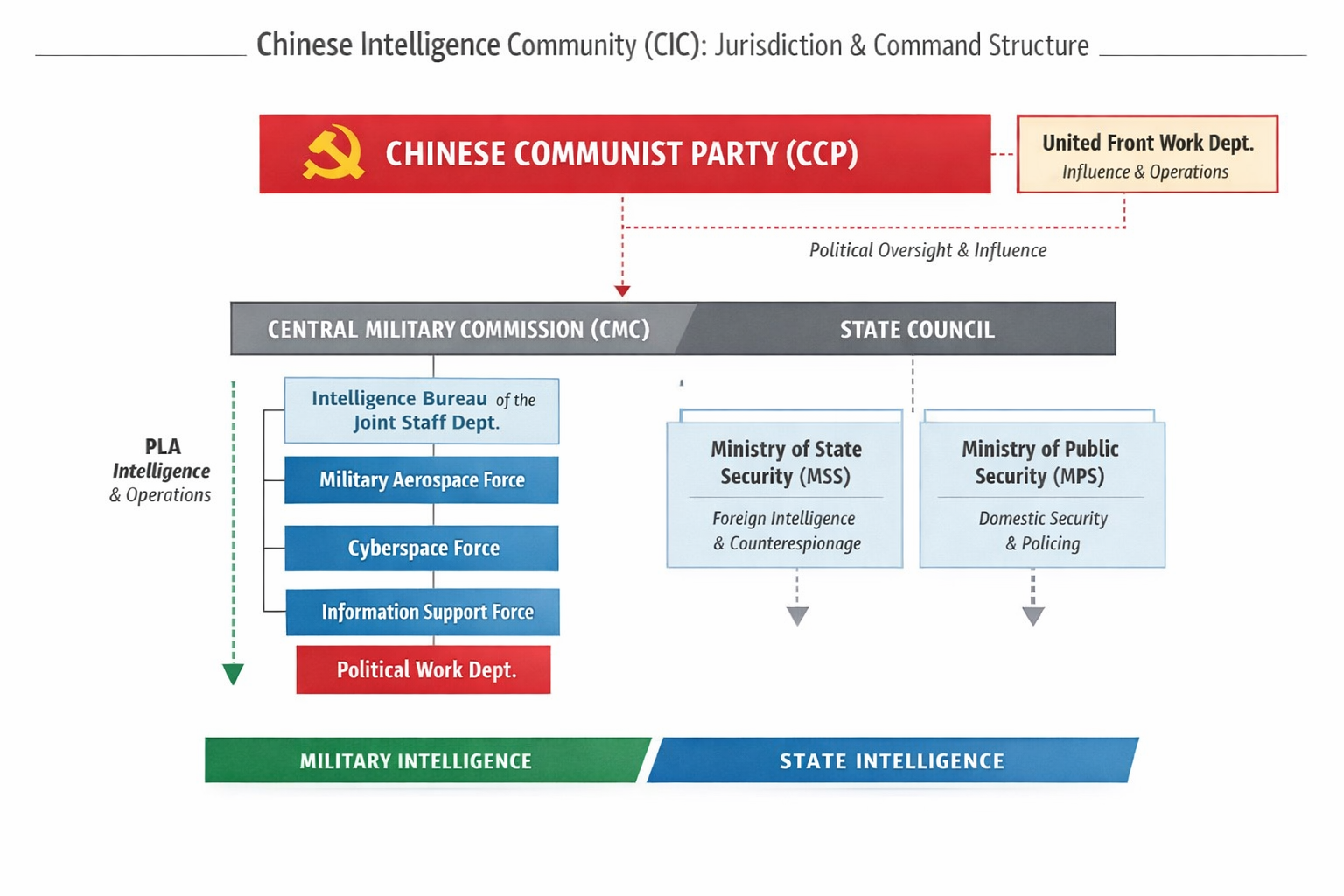

3.0 Three-Headed Dragon

In this context of integrated state and intelligence apparatuses, this article will examine the architecture of the CIC under the three specific heads of each branch: the Chinese Government, the PLA, and the CCP. In this section, we will provide a command structure outline of how power and command flows through the CIC architecture.

Jurisdiction and political control over the CIC is a critical issue for President Xi Jinping, and this principle has guided his massive reforms since he took office in 2012. For Xi, the PLA and, in extension, the intelligence apparatus are underprepared to act, and are not yet an effective fighting force. The CIC is tangent to this line of thinking, even though it may not be directly targeted by Xi’s flurry of purges. The sheer size, breadth and complexity of the functions and responsibilities of the CIC’s many agencies demand a certain degree of flexibility but also a clear understanding of who calls the shots. For this reason, it is crucial to understand the structure and use that each branch has for the agencies under its jurisdiction.

Ultimately, China’s Intelligence Community is not a single hierarchical organization, but a Party-dominated ecosystem in which military, civilian, and political intelligence organs operate in parallel under centralized CCP control.

CIC: Jurisdiction and Command Structure Diagram

3.1 The Chinese Government

Under the Chinese government, intelligence authority is exercised primarily through the Ministry of State Security (MSS) and the Ministry of Public Security (MPS). Both operate within the State Council system but are ultimately subordinated to CCP political leadership. The MSS serves as the PRC’s principal civilian intelligence and counterintelligence organ. It is responsible for foreign intelligence, political security, and internal threat suppression. On the other hand, the MPS retains broad domestic security, policing, and counter-subversion responsibilities.

Jurisdictionally, the boundary between the two is deliberately blurred. Intelligence collection, surveillance, and political security functions frequently overlap, particularly in areas such as technology acquisition, diaspora monitoring, and counter-espionage. This leads to a layered but redundant civilian intelligence environment. Therein, regime security is privileged over bureaucratic clarity. Nevertheless, this enables Beijing to mobilize both overt law-enforcement and covert intelligence tools to tackle any threat it deems critical.

[source]

3.2 The People’s Liberation Army

Within the PLA, intelligence and information power are currently organized under a restructured, CMC-centric command system. This reflects the post-2024 emphasis on domain specialization and political control. Intelligence-relevant functions are distributed across the Military Aerospace Force, Cyberspace Force, and Information Support Force, each responsible for their respective operational domains while remaining directly subordinate to the CMC rather than a unified service.

Alongside these, the Political Work Department (PWD) plays a critical intelligence role, overseeing political reliability, influence operations, and internal monitoring within the PLA. This arrangement embeds intelligence as an enabling function of joint warfare. At the same time, it ensures that information dominance, political control, and operational command converge at the CMC level. This reduces institutional autonomy within the PLA intelligence ecosystem.

3.3 The Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party exerts intelligence authority not through formal state command but via political supervision and influence mechanisms. Most notably this is done through the United Front Work Department (UFWD). The UFWD operates as the Party’s primary instrument for influence, co-optation, and information gathering among non-Party elites. It also overseas Chinese communities abroad, foreign political actors, and social organizations.

While not an intelligence service in the traditional sense, it functions as a strategic enabler of China’s Intelligence Community. It generates access, shapes narratives, and creates permissive environments for both civilian and military intelligence operations. Its position within the Party hierarchy, which is outside conventional state oversight, underscores a defining feature of the CIC. Ultimate intelligence authority rests with the CCP, not the government or the military. This ensures that intelligence serves long-term political objectives as much as immediate security needs. Political survival is a critical issue of national security for the PRC, and this is simply another element that highlights this principle.

4.0 CIC: The Arms of the Agencies

In this section, the analysis will examine the individual agencies within China’s Intelligence Community. This will include an evaluation of their profiles, goals & purpose, along with their modus operandi. MO will address known ways of operating, tools of trade, targets, and specific details pertaining to each agency and its profile.

4.1 Ministry of State Security

The Ministry of State Security (MSS) stands at the core of China’s civilian intelligence architecture. It is best understood as an amalgam of the CIA and the FBI. Established in 1983 the MSS combines foreign intelligence collection, domestic counterintelligence, political security, and regime protection within a single institution.

The MSS operates without meaningful judicial oversight and is embedded in a legal environment that subordinates law to political necessity. This allows it to move fluidly across intelligence, law enforcement, and coercive security roles. The MSS is the most secretive of agencies within the CIC. Therefore information regarding its structure and operations is well guarded and difficult to corroborate.

4.1.1 MSS Structure

Organizationally, the MSS is structured in approximately 16 to18 internal bureaus. Each is broadly aligned with functional, geographic, or technical missions. While official disclosures remain sparse, our analysis suggests these bureaus cover foreign intelligence by region, counterintelligence, political security, cyber and technical intelligence, analysis, and internal discipline.

This bureau-based structure allows the MSS to compartmentalize operations while maintaining centralized political control from Beijing. In practice, local MSS units function as both intelligence collectors and political enforcers, tightly integrated with central priorities rather than local governance concerns.

4.1.2 MSS Mission

The MSS’s mission focuses around countering what the CCP terms the “Five Poisons.” These are:

- Uyghur separatism in Turkestan

- Tibetan independence movements

- Adherents of the Falun Gong cult

- Political/ democratic opponents within China

- Taiwanese independence advocates

The concept of the Five Poisons provides the ideological justification for a wide operational remit. This enables the MSS to treat foreign intelligence services, dissident groups, NGOs, religious movements, and even academic exchanges as interconnected threats.

Chinese intelligence strategy, legalized through the reforms in 2017, does not sharply distinguish between internal and external adversaries. Rather, it views them as part of a single hostile system seeking to undermine Party rule. In this context, the MSS functions as both an intelligence service and a political shield. It preempts threats before they mature rather than merely responding to them.

The MSS’s mission includes cooperation with other security and law enforcement bodies to achieve its goal. This is true particularly for collaboration with the Ministry of Public Security (MPS). In its collaborative roles, the MSS mainly targets the drivers of political threat. However this division of labor is not rigid. Joint tasking, shared intelligence, and overlapping authorities are common. This is especially true in politically sensitive cases involving academics, journalists, ethnic minorities, or foreign-linked organizations. This creates a dense internal security web in which intelligence and policing reinforce one another.

4.1.3 MSS Operational Profile

Operationally, the MSS engages deeply in both foreign intelligence and counterintelligence. There is a particular emphasis on long-term penetration rather than short-term collection. Its modus operandi favors human intelligence cultivation, non-official cover, academic and commercial access points, and the exploitation of diaspora networks.

The MSS focuses on strategic intelligence, technology acquisition, elite influence, and political threat neutralization. In the cyber domain, the MSS has increasingly relied on contractor ecosystems and semi-deniable actors, such as computer hacking groups (APTs). This blurs the line between state intelligence operations and criminal or quasi-commercial intrusion activity.

Ultimately, the MSS exemplifies the defining characteristics of China’s Intelligence Community. It features centralized political control, expansive legal authority, and a fusion of intelligence with regime security. Its power lies in its ability to mobilize state, society, and law in service of intelligence objectives. For foreign governments and institutions, the challenge posed by the MSS is not simply espionage. It is a persistent, adaptive, and ideologically driven intelligence actor operating across diplomatic, economic, academic, and technological domains simultaneously.

4.2 Ministry of Public Security

The Ministry of Public Security (MPS) is the primary civilian national police authority of the People’s Republic of China. It is primarily responsible for enforcing public order, internal security, and the rule of law across the country. As a constituent ministry of the State Council, the MPS leads and coordinates China’s vast network of public security organs including the People’s Police. It collectively numbers nearly 2 million officers and operates from the national level down through provinces, prefectures, counties, and local substations. Its Minister, who typically holds the rank of State Councilor and also serves as deputy secretary of the CCP’s Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission.

4.2.1 MPS Structure

Structurally, the MPS contains a General Office and over 20 internal bureaus tasked with specialized functions ranging from routine policing to political security. Among these, the Political Security Protection Bureau (1st Bureau) focuses on identifying, monitoring, and neutralizing perceived political threats and subversive activities domestically. Other functional bureaus include those dedicated to criminal investigation, public order, border and immigration control, traffic and transport safety, economic crime, and cybersecurity monitoring and enforcement. Hierarchically, the MPS exercises centralized leadership and operational guidance over provincial public security departments and municipal public security centers.

4.2.2 MPS Mission

The MPS’s mission encompasses crime prevention and investigation; counter-terrorism; anti-smuggling and cybercrime operations; border security and immigration administration; and the maintenance of public order and social stability. It manages legal issues such as household registration (hukou), national identity cards, citizenship matters, and foreigner entry–exit and residence affairs. The ministry also guides public security work in government institutions, enterprises, and mass organizations.

4.2.3 MPS Operational Profile

The MPS functions as China’s frontline internal security force. Its local public security bureaus handle routine policing, traffic and transport regulation, household registration oversight, and neighborhood safety operations, but also increasingly mobilize for politically sensitive tasks. This includes crowd control, suppression of unauthorized demonstrations, anti-terrorism campaigns, and “stability maintenance” operations.

The MPS also collects information on political dissent, social movements, and organized crime. It integrate these insights into both preventive policing and political security strategies. Additionally, the MPS plays a growing role in cyber enforcement and public information network monitoring. The MPS exercises legal authority to combat cybercrime and supervise digital platforms under the broad umbrella of “public security.”

It interacts closely with other security organs, most notably the MSS on matters of internal counterintelligence and political protection. This blend of traditional policing, administrative control, political surveillance, and information gathering positions the MPS as a central pillar of domestic intelligence and coercive capacity. The MPS is able not just to enforce laws but to preempt and neutralize threats to social stability and CCP authority.

4.3 Intelligence Bureau of the Joint Staff Department

The Intelligence Bureau of the Joint Staff Department (JSD) serves as the principal military intelligence organ of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Formerly the Second Department of the General Staff Department (2PLA), it reorganized in January 2016 as part of sweeping CMC-led military reforms.

The Intelligence Bureau consolidates the strategic, human-centric intelligence functions under a unified joint command structure that is directly responsible to the CMC through the JSD.

Operationally, the Intelligence Bureau conducts human intelligence operations abroad, manages the PLA’s defense attaché network, and produces intelligence for senior leadership and operational planners. Its modus operandi emphasizes long-term access, elite-level penetration, and persistent intelligence coverage of priority military targets rather than tactical battlefield collection.

The Bureau’s placement within the JSD reflects its role as a decision-support engine, ensuring that intelligence feeds directly into joint planning and campaign design. In the post-2024 PLA architecture, it occupies a complementary position to the Cyberspace and Aerospace Forces. The Intelligence Bureau focuses on high-profile espionage and infiltration (including against critical infrastructure targets).

[source]

4.4 Military Aerospace Force

The PLA’s Military Aerospace Force (MAF) is a strategic military intelligence and space operations service established on 19 April 2024. Although the name might superficially resemble the Air Force, the MAF is not an aviation service. It is best understood as the PLA’s space intelligence and aerospace domain force. As such, it is responsible for space-based surveillance, domain awareness, precision targeting support, and space control missions.

Significantly, the MAF inherits much of its personnel, culture, and operational competencies from the PLA’s former Third Department (3PLA) and Fourth Department (4PLA). These were the PLA’s legacy signals intelligence (SIGINT), electronic intelligence (ELINT), and electronic warfare organizations, as well as space and aerospace units previously aligned under the General Armaments Department (GAD) and later consolidated under the SSF. This lineage roots the MAF in a technical intelligence tradition rather than conventional air combat or tactical support.

Through the MAF, the PLA has emphasized that space and aerospace intelligence are strategic, cross-service capabilities rather than service-specific add-ons.

4.4.1 MAF Structure

According to Jamestown Foundation analysis, the MAF’s internal organization revolves around seven principal “space bases.” Each acts in specialized functions critical to space intelligence and mission support. These bases reflect a strategic-function orientation, instead of a geographic alignment. Thus, this assortment underscores the MAF’s role as a centralized national intelligence capability rather than a regional force.

- Base 23 — China Satellite Maritime Tracking and Control Department: Operates the PLA’s maritime telemetry, tracking, and control network. Crucial for global satellite operations.

- Base 25 — Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center: Executes strategic satellite launches, including reconnaissance and earth observation platforms.

- Base 26 — Xi’an Satellite Control Center: Central node for telemetry, tracking, command, and control of satellites. This integrates space operations across global ground stations.

- Base 27 — Xichang Satellite Launch Center: Handles geostationary and high-orbit launches, including communications and ISR payloads. Its facilities also supported China’s first anti-satellite test.

- Base 35 — Battlefield Environment Support Base: Consolidates geospatial mapping, navigation, and positioning missions.

- Base 36 — Kaifeng Base: Focuses on space equipment R&D, testing, and evaluation, including advanced space technologies and counter-space systems.

- Base 37 — Early Warning Base: Central to space situational awareness (SSA), ballistic missile early warning, and tracking foreign satellites and debris. Often operating large phased array radar networks.

Specialized bureaus and centers such as the Aerospace Reconnaissance Bureau, Beijing Aerospace Flight Control Center, and various research institutes complement these bases and support both intelligence collection and mission execution.

4.4.2 MAF Mission

The MAF exists to ensure the PLA’s space domain awareness, strategic early warning, precision targeting, and space control in the context of great-power competition. This is particularly true against the United States and in a contingency involving Taiwan or the South China Sea.

The force’s functions serve three overarching purposes:

- Space-based Intelligence and Surveillance: providing observation, tracking, and data collection on foreign military movements and space activities.

- Integrated Targeting and Early Warning: feeding real-time or near-real-time data into PLA targeting and missile warning systems.

- Space Control and Counter-Space Operations: including denial of adversary space capabilities.

The MAF’s focus is domain control and intelligence support across all joint operations, especially where space superiority supports precision strikes, communications, and battlefield awareness.

4.4.3 MAF Operational Profile

The MAF’s modus operandi reflects its identity as a military intelligence service. Its operational profile includes:

- Persistent Space Surveillance: using constellation tracking, telemetry networks, and optical/electronic sensors to maintain a continuous picture of the space domain.

- Data Fusion and Targeting Integration: Intelligence from space sensors systematically integrated with PLA targeting architectures, enhancing the speed and accuracy of joint fire and missile systems.

- Early Warning & Ballistic Tracking: Base 37’s SSA and early warning responsibilities feed into China’s strategic deterrence posture by reducing decision timelines and increasing warning confidence.

- Counter-Space Activities: offensive and defensive classed counter-space missions — including jamming, co-orbital interference, and potential directed-energy systems — while maintaining strategic ambiguity.

This fusion reflects a broader PLA doctrinal shift toward domain-integrated joint warfare, in which data from space intelligence directly fuels command-and-control cycles throughout conventional domains.

The establishment of the MAF in 2024 signals a strategic prioritization of space intelligence as a foundational element of Chinese military modernization. The MAF reprsents an institutionalization of space as a critical intelligence battlefield. The MAF’s direct subordination to the CMC and its centralized base structure suggest Beijing’s intent to reduce inter-service friction and accelerate decision cycles in future high-intensity conflicts. The MAF functions as the PLA’s strategic space intelligence arm. It amplifies China’s ability to integrate space-derived data with joint force execution.

[source]

4.5 Cyberspace Force

The PLA’s Cyberspace Force (CSF) was established in April 2024 following the dissolution of the SSF. This move consolidated the PLA’s cyber and network warfare capabilities into a dedicated service arm directly subordinate to the CMC. The CSF inherits the core mission sets of the former SSF Network Systems Department, itself the institutional successor to the historic 3PLA and 4PLA. As such, the CSF is best understood as a strategic military intelligence and information warfare organization operating in the cyber and electromagnetic domains.

4.5.1 CSF Structure

CSF is organized as follows, according to Jamestown research, along regional Technical Reconnaissance Bases (TRBs). Each of these generally aligns with a PLA military theater. Their purpose is to consolidate technical intelligence functions formerly scattered across PLA services and regions.

- Eastern Technical Reconnaissance Base (Unit 32046) — Nanjing (Eastern Theater)

- Southern Technical Reconnaissance Base (Unit 32053) — Guangzhou (Southern Theater)

- Western Technical Reconnaissance Base (Unit 32058) — Chengdu (Western Theater)

- Northern Technical Reconnaissance Base (Unit 32065) — Shenyang (Northern Theater)

- Central Technical Reconnaissance Base (Unit 32081) — Beijing (Central/Joint Area)

Each TRB comprises multiple subordinate offices responsible for localized cyber intelligence collection, technical reconnaissance, and targeting support across its theater area.

Along with these five is the Cyberspace Operations Base (CSOB). This unit is a national-level, Corps Leader–grade organization that sits alongside the regional TRBs as the PLA’s central cyber operations hub.

The CSOB consolidates disparate cyber espionage, offense, electronic warfare, psychological operations, and cybersecurity technology units. These were previously scattered across the former 3PLA, 4PLA, PLAAF, PLAN, PLARF, and other military elements.

Within the Operations Base itself, the force is organized around a four-part force structure reflecting functional priorities:

- Cyber warfare units — network exploitation and attack.

- Electronic warfare forces — system jamming and denial.

- Psychological warfare elements — information and cognitive operations.

- Cyber research & development — tools, exploits, and advanced capabilities development.

4.5.2 CSF Mission

The CSF’s primary purpose is to secure PLA dominance in the information domain, which Chinese military doctrine treats as a decisive battlespace in modern warfare. Its responsibilities include cyber reconnaissance, network exploitation, electronic warfare coordination, and both offensive and defensive cyber operations. Rather than acting independently, the CSF functions as an enabling force. Jamestown analysis characterizes the CSF as a “bellwether” force, reflecting the PLA’s expectation that cyber operations will feature prominently in the opening phases of any high-intensity conflict .

In operational terms, the CSF emphasizes persistent network access, long-term reconnaissance, and pre-conflict shaping of adversary information systems. Its modus operandi prioritizes stealth, endurance, and strategic preparation rather than overt disruption.

[source]

4.6 Information Support Force

The Information Support Force (ISF) is a brand-new strategic arm of the PLA, established on 19 April 2024. It was created concurrent with the dissolution of the SSF alongside the MAF, CSF and the Joint Logistic Support Force.

According to the Chinese Ministry of National Defense, the ISF is critical for coordinating the construction and application of the PLA’s network information systems, ensuring information flow, integration of information resources, and protection of information security across the joint force. Its core functions include command, control, communications, computing, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR).

Xi Jinping’s statements emphasize that the ISF is not merely a technical support entity, but a core pillar of the PLA’s ability to “fight and win” in modern warfare, reflecting China’s broader doctrinal shift toward informationized and intelligentized operations.

The ISF is positioned at the deputy theater command grade, equivalent in status to the MAF and CSF but distinct from traditional PLA service branches (Army, Navy, Air Force, Rocket Force). Its leadership includes a commander and a political commissar, reflecting the PLA’s dual military–political command model.

[source, source, source, source]

4.7 Political Work Department

The Political Work Department (PWD) is the PLA’s principal Party control and political security organ. While not an intelligence service in the conventional sense, the PWD performs critical intelligence-adjacent functions related to personnel monitoring, internal security, loyalty enforcement, and influence operations within the PLA. It oversees political commissars at every echelon, manages political discipline and vetting, and maintains responsibility for counter-subversion, morale, and ideological conformity. In this capacity, the PWD acts as the PLA’s internal control mechanism, ensuring that military power remains firmly subordinated to the CCP.

Beyond internal oversight, the PWD plays an enabling role in political warfare and influence operations, particularly in support of broader United Front and strategic messaging efforts. Its responsibilities include psychological operations, propaganda, and the political preparation of the battlespace, often coordinated with other PLA information forces during joint campaigns. The PWD highlights that information superiority is inseparable from political control for the PLA.

4.8 United Work Front Department

The United Front Work Department (UFWD) is a Central Committee organ of the Chinese Communist Party responsible for outreach, influence, and political intelligence activities that extend far beyond traditional propaganda or cultural diplomacy. It operates as the CCP’s principal mechanism for engaging, co-opting, and monitoring individuals and organizations outside formal party structures.

4.8.1 UWFD Structure

Unverified sources report that the UWFD is organized around multiple bureaus and through several institutions which are affiliated with it, including some universities, publishing organizations, groups etc. These are:

- General Office: Oversees the functioning of the department, including its finances, security, assets, and work with other government and Party bodies.

- Policy and Theory Research Office: Handles ideological and policy research, internal propaganda, and the drafting of important documents.

- First Bureau: Governs affairs related to the eight minor political parties legally allowed to operate in China.

- Second Bureau: Researches and recommends policy on minorities in the country. Liaises with other government agencies in their related work.

- Third Bureau (Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan United Front Work Bureau): Coordinates and communicates with friendly figures in Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan.

- Fourth Bureau (Non-public Economic Work Bureau): Coordinates with figures from the private sector.

- Fifth Bureau (Independent and Non-Party Intellectuals Work Bureau): Liaises with non-Party intellectuals.

- Sixth Bureau (New Social Class Representatives Work Bureau): Focuses on the “new social class”, i.e., the rising Chinese middle class.

- Seventh Bureau: Responsible for ethnic minority and religious work, particularly as it relates to Tibet.

- Eighth Bureau: Responsible for ethnic minority and religious work, particularly as it relates to Xinjiang.

- Ninth Bureau (Overseas Chinese Affairs General Bureau): Coordinates and communicates with friendly figures in overseas Chinese affairs. It runs the China Overseas Friendship Association (COFA), which merged with the China Overseas Exchange Association (COEA) in 2019.

- Tenth Bureau (Overseas Chinese Affairs Bureau): Coordinates and communicates with friendly figures in overseas Chinese affairs.

- Eleventh Bureau (Religious Work General Bureau): Researches and recommends policy on religious affairs in the country. Liaises with other government agencies in their related work.

- Twelfth Bureau: adjacent or similar to the Eleventh Bureau.

- Department Party Committee.

- Retired Cadre Office: responsible for the welfare of retired employees of the department.

[source]

4.8.2 UWFD Mission

At its core, the UFWD gathers intelligence on elite individuals and influential organizations in mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and across the globe. These targets typically include business leaders, academics, media figures, religious leaders, ethnic diaspora elites, and community organizations.

Through engagement, networking, and cultivation, the UFWD seeks both access to actionable information and long-term political leverage, but also to conduct offensive covert operations and divide, undermine or terminate threats.

4.8.3 UWFD Operational Profile

The department compiles extensive information on political, commercial, and academic elites by tracking their influence, affiliations, and susceptibility to CCP messaging. This is effectively both political intelligence and influence management. The UFWD targets the overseas Chinese diaspora, engaging individuals and groups through cultural associations, business networks, student organizations, and community bodies. This helps to build pro-Beijing sentiment and pre-empt criticism of CCP policies. It both cultivates supporters and works to divide and weaken potential critics abroad.

At the same time, influential overseas individuals may be offered recognition, patronage, economic engagement, or speaking platforms in exchange for alignment with CCP priorities. This allows the UFWD to create networks of loyalty or strategic influence across foreign landscapes.

A strategic component of UFWD work is leveraging networks that blur the lines between civil, economic, and criminal spheres. Some overseas networks with roots in Hongmen and associated associations have been mobilized under United Front guidance to support CCP goals such as reunification narratives and community control. Connections with criminal organizations and groups, such as the Triads, also exist within the UFWD’s toolkit.

[source, source, source, source, source]

5.0 Conclusion

China’s Intelligence Community is a highly organic, at times redundant, but well-interconnected system. It has multiple points of overlap between civilian, military, and Party organs. Redundancy is not always inefficiency. At times, it is a deliberate feature that strengthens resilience, ensures coverage across domains, and allows intelligence to flow through multiple channels.

Reforms since 2015 have sought to streamline bureaucratization and embed agencies firmly under political control, not primarily through commissarial-style enforcement, although such mechanisms remain in place. By institutionalizing authority through legal frameworks, command structures, and organizational design, Beijing has created a system in which oversight and obedience are built into the architecture itself rather than imposed episodically.

The importance of intelligence across military, state, and civilian applications in China reflects a whole-of-society approach. The agencies of China’s Intelligence Community often operate in parallel and in coordination, covering political, technological, strategic, and influence domains simultaneously. The organization, structure, and activities of the CIC demonstrate this coherence clearly. Intelligence is not simply about collection or counterintelligence, but about ensuring Party control, strategic advantage, and societal alignment. China’s Intelligence Community is not a set of separate services. It is a unified ecosystem optimized to see broadly, act persistently, and reinforce the CCP’s authority at every level.