Far from having a straightforward definition, International security is a multifaceted concept that includes both traditional concerns with terrorism, insurgency and war, but also interests in other fundamental dimensions of people’s life. In particular: the economy, the environment, health, and food.

At the same time, the vastness of sub-Saharan Africa encompasses a multiplicity of novel experiences and contradictory dynamics that cannot be easily reduced to direct causal relationships.

To decipher the complex relationship between international security and Sub-Saharan Africa, Samuele Minelli, an analyst at Grey Dynamics, interviewed Dr. Niamh Gaynor, professor of Politics and Development in Sub-Saharan Africa at Dublin City University who brilliantly combines theoretical and first-hand practical expertise. Her research focus concerns development politics and governance, local-regional conflicts and non-traditional security issues.

1. Where does your passion in sub-Saharan Africa come from? What are the main projects in which you have participated over the last years?

I’m not entirely sure where my passion for Sub-Saharan Africa comes from. It has been a long time since I started working on the continent. So, I suppose that my interest in the region developed when I went to Ethiopia in the mid-nineties to do research for my master’s degree focusing on rural development, local conflict and ethnic issues. At that time, I thought that you could grow more and that would solve food security problems. By the time I finished my degree, unfortunately, I had learned that food insecurity is a political issue. There is enough food to feed the world many times over.

After that, I lived in Benin for three years working for the German Agency for International Development (GIZ). This experience taught me a lot. It was a broad integrated project in a rural area near the border with Burkina Faso about natural resource management and climate change involving different ethnic communities. So, I became aware of how ethnic tensions can be mobilized and develop into international security issues.

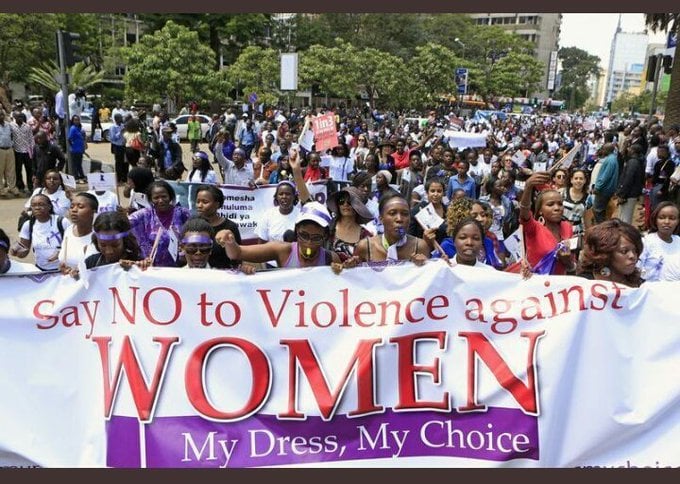

Then, I focused more on the interaction between politics and development. During this period, I worked in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda and Burundi on NGO projects concerned with local governance, decentralization, and peacebuilding. Later, I worked in Ituri, in the northeast of the DRC with different community groups trying to reduce ethnic tensions, sadly unsuccessfully. In the last years, I collaborated with Action Aid in Malawi on gender-based violence, and I had plans to go to Kenya for a programme dedicated to local development and women empowerment, but the Covid pandemic started.

3. Is it possible to identify macro-trends regarding international security and sub-Saharan Africa? Which are the main threats to the continent’s peace?

That’s a big question. But I pulled out four main factors. I think poverty and inequality are key drivers of local conflicts. I’ve seen this everywhere I’ve been. In particular, inequality, whether perceived or real, fuels grievances that can contribute to low-intensity local violence, but also can be mobilised internationally.

Additionally, climate change is playing a harmful role in certain parts of sub-Saharan Africa. For instance, if you take South Sudan, if there wasn’t land scarcity, there wouldn’t be as much conflict. Unfortunately, climate transformations are only worsening the situation.

There is not enough attention on International political economy. For example, if I take my work in Ituri with local community groups. We were there trying to avoid another big ethnic conflict, while the internationally linked resource entrepreneurs were responsible for fomenting all those tensions around oil and gold extraction near Lake Albert. Even during COP 27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, while negotiating about reducing emissions. Several western countries signed deals for oil and gas in many countries, including Sub-Saharan Africa. Another linked element is tax avoidance from various international corporations that extract wealth, almost expropriating resources. All of this feeds inequality, poverty, displacement and unrest.

Finally, the last element is growing authoritarianism among African political leaders. In a number of countries, Covid exacerbated the situation. For instance, just in the last two years, there have been six successful coups and as many attempts in sub-Saharan Africa. In particular the situation in the Western Sahel is worrisome.

4 Could you briefly define the human security framework? How much is possible to apply it in African contexts, and what is its relevancy for international security?

The human security framework is usually attributed to the United Nations (UN) back in 1994. Due to its dissatisfaction with the militaristic parameters of the traditional security approach, human security emphasised the interlinkages between development and insecurity. They outlined seven dimensions of insecurity, covering a broad range of issues:

- Economic security,

- Food security,

- Health security,

- Environmental security,

- Personal security

- Political security

Despite the criticisms, I think it is very applicable to Sub-Saharan Africa. For example, if you take personal security, I remember when I was in Burundi in the aftermath of a devastating civil war that caused 300,000 deaths. I was asking people, what did peace mean to them? What was important for them? Again and again, people, particularly women, said to be able to just walk to the market and not be attacked. It’s a huge thing that we all take for granted. And you know, when we talk about drones or bombs or whatever it is, we forget about people’s real lives and the everyday.

Land security is hugely important. In DRC, there have been so many conflicts over land. Any traditional local authority will tell you this is the key thorny issue in the area, and the low-intensity violence can easily escalate.

5. How much do foreign countries influence the African Continent? What is their impact on international security?

They have a big impact. There are three main dimensions. As I have already mentioned, there is not enough consideration of the international political economy dimension. Several conflicts, such as in the Horn of Africa, are not about ideology anymore, they’re about business. It’s about money and greed. Besides, the peace-keeping missions’ impact on the continent is also relevant. Finally, the aid industry has a massive influence on both the government and societies more broadly.

However, which impact do they have? Simultaneously positive and negative. Foreign country investment can bring prosperity, growth and job opportunities. The aid industry can alleviate poverty in small pockets, albeit it can’t bring development, broadly speaking. But, at the same time, it can also lead to dependency. Governments can become more accountable to donors than to their people, thus triggering negative implications for democracy.

From their side, Peacekeepers can protect civilians and can make guns fall silent for a while. But you can also have the negative as well. I think particularly that kind of militarised culture, has lasting legacies on places feeding instability.

6. Since poverty characterises violent and peaceful contexts, which role plays development over security? Is there any causal relationship between the two?

That is a very intriguing question. You can’t contest the fact that when there is violence, it leads to widespread displacement. Besides, crops aren’t grown, bringing food insecurity. If social services break down, people lose jobs. So, certainly know that conflict leads to the fall of development indicators while raising inequality and poverty.

Nevertheless, the other direction also holds, when people feel that there is inequality or discrimination, they become more easily mobilized. They can have grievances against their same neighbours. I saw this in particular in Bas-Congo, a relatively small region in western DRC that used to be very wealthy during colonial times. Everybody I spoke to was very disaffected because of the diminishment of wealth after the Belgians’ departure. People were fighting with their neighbours, everybody had little arguments with everybody else and everybody was living a little bit on the edge. It was only waiting to escalate into something more even if poverty wasn’t as great compared to other DRC regions.

Therefore, we could say that poverty and inequality lead to unrest and conflict but need other dimensions to be there, such as ethnic tensions. For example, Malawi has never really this kind of friction, not even in terms of religion. In the country coexist both Christians and Muslims but there has never been a problem. I would say also that the aid industry plays a positive role there. Malawi is very aid-dependent, so people in abject poverty get assistance. Whereas, Somalia has been kind of left. Governance is another issue. Whilst Malawi is a reasonably stable democratic state, Somalia would be seen as a kind of space difficult to govern.

7. There is much debate about the effectiveness of peace missions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Which are their main strengths and weaknesses? If you could reform them, which changes would you propose?

Since 1960, there have been more than 30 UN peacekeeping missions, half of them there have been in sub-Saharan Africa. For instance, the mission in DRC (MONUSCO) is the most expensive UN mission there’s ever been. In terms of their strengths, they can have a positive impact on stopping bloodshed and temporary stabilisation which makes a big difference in people’s lives. In particular, I think the operation in Sierra Leone and Liberia are generally regarded as quite successful in terms of protecting civilians, also because the warring parties actually wanted to end the hostilities. On the other hand, the continent is littered with, not-so-successful peacekeeping operations. Probably one of the main issues is that peacekeeping missions focus on short-term stability and not on long-term peace-building, that would require significant investments of time and resources.

Besides, in some situations such as in DRC, the missions tend to reward rebels. Indeed, the rebels’ condition potentially shifts from extracting wealth through violence to getting governorship positions in the provincial administration. Obviously, this continues the perpetuation of sick power relationships in a legal political structure. Another issue is that the UN missions tend to be very top-down. The mission arrives on-field and decides what is more appropriate to do without consulting the locals to understand what they need. Moreover, they are often poorly managed, and the mandate is not always clear.

Additionally, there have been documented incidences where even the mission itself has started to take sides. For example, the African Union has been accused of taking sides in conflicts, and it’s supposed to be. Then, in various situations, the peacekeepers have abused the population, and the dysfunctional accountability system does not allow to pursue them properly.

Regarding the reform potential. I would suggest addressing more directly the key drivers of conflict and not only temporarily stopping violence. Secondly, to improve leadership and accountability. Finally, I would argue for more female peacekeepers and support structures to change the culture a little bit.

8. How relevant is the gender dimension in international security?

War leads to increasingly militarised cultures. So, in places where you have unrest, you have many guns. There can be tanks patrolling around. At seven o’clock every morning, these big tanks go around with these guys, with these big guns contributing to the militarisation of the environment. Again, having more female peacekeepers would help combined with an environment in which they would be happy to work.

Regarding the peace processes, there have been improvements in involving women in negotiations. Peace negotiations in the past just involved a group of men standing around the table, while totally excluding women. Thus marginalising a important group in the long-term perspective of the peace process.

Of course, gender is not just about women, it’s also about men. So, one issue that feeds into insecurity is the prevalent view that a man’s role is to be the family’s breadwinner. Therefore, when a father cannot afford to put food on the table, the community starts to belittle him. This actually can spill out into gender-based domestic violence and broader violence as well.

9. Which role is playing and will play climate change on the international security of the continent?

Climate change is one of the key conflict drivers. Already several conflicts are exacerbated by the scarcity of resources, and due to climate change, those are becoming even more scarce, rising the competition for them. The Horn of Africa is a relevant example. Indeed, in the last years, droughts’ occurrence has rised significantly causing displacement and acting as a threat multiplier for conflict over land.

Land grabs are strictly linked to environmental crisis. International companies take large land tracks to produce food for other parts of the world or biofuels. Paradoxically, this is all part of the Western strategy against climate change, but it involves grabbing resources that impact sub-Saharan Africa’s environment and stability.

African countries are among the most adversely affected by climate change but the funding for adaptation is woefully short of what has been pledged by the global North. As long as there isn’t adaptation funding and western countries, continue with the carbon output that they have, I can’t see it getting any better.

10. What prospects do you foresee for sub-Saharan Africa peace and security?

Unfortunately, there are many negative trends. We live in a very interconnected world, and the Covid pandemic hardly hit sub-Saharan Africa. Indeed, even if poverty was generally reducing, since Covid started rising again. Similar tendencies are recorded for inequalities introducing a potentially dangerous factor. Big gaps between rich and the poor fuel grievances and facilitate destructive social dynamics. Additionally, several leaders across the continent used the pandemic as an excuse to enhance the centralisation of power. This growth in authoritarianism has been accompanied by dissent repression.

Nevertheless, there are also positive sides. For instance, the young population, a labour reserve that can bring about a higher level of development, also positively impacts peace and security. Finally, social media usage is rising, especially regarding Facebook and Twitter. Despite some downsides, several social media campaigns have brought change responding to people’s disquiet and keeping politicians more accountable. For instance, land grabbing reporting, the Kenyan Twitter campaign titled “my dress, my choice”, and the sensitisation against gender-based violence in Nairobi have rised government awareness around fundamental problems. Especially if linked internationally, these networks can put pressure on various relevant issues related to peace and security, bringing positive change to the whole continent.