This Grey Dynamics African intelligence article analyses the misinformation war between Russian and French troll-on-troll actors. It is important to assess the differences in Russian and French information campaigns, but to note the similarity when engaging with one another.

Key Findings

- December 2020. Facebook removes troll accounts / groups linked to individuals associated with the French military and Russian Internet Research Agency “troll farm”.

- The operations focus on influencing public opinion in targeted African countries, such as the Central African Republic (CAR) and Mali. In CAR and countries with contested interest, the primary focus is displaying the adversary in a negative perspective, while displaying themselves positively.

- Russian and French troll-on-troll operations, in an unprecedented move, openly target and engage with each other with ironic ‘fake news’ exposés.

- Russian operations can likely be judged as more effective. Creditable to the gap in information warfare experience and incorporation of local nationals into the networks for authenticity.

- While French operations were likely influenced by existing Russian troll farms, countering trolls vis-à-vis is problematic and counterproductive. By mirroring inauthentic entities and individuals, this revelation increases public distrust of genuine news outlets and supports a stimulated climate of ‘fake news’.

Russian Campaign

The Russian information campaign in Africa is an extensive and well-established layer of increased engagement within African countries. In Africa, Russia has much to gain. A growing weapons export market, natural resources, and increasing geopolitical influence. Yevgeniy Prigozhin, founder of the Wagner mercenary group and Internet Research Agency (IRA) continues to be linked to ‘troll farms’ in Africa. In the case of Africa, the aim of psyops is manipulating public narrative in favour of Russian presence and activities. IRA activities have been identified in Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, CAR, Libya, Ukraine, the US, and beyond. In 2019, Facebook accounts linked to the IRA were taken down in Madagascar, CAR, Mozambique, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Sudan, and Libya. This did not stop the creation of new accounts.

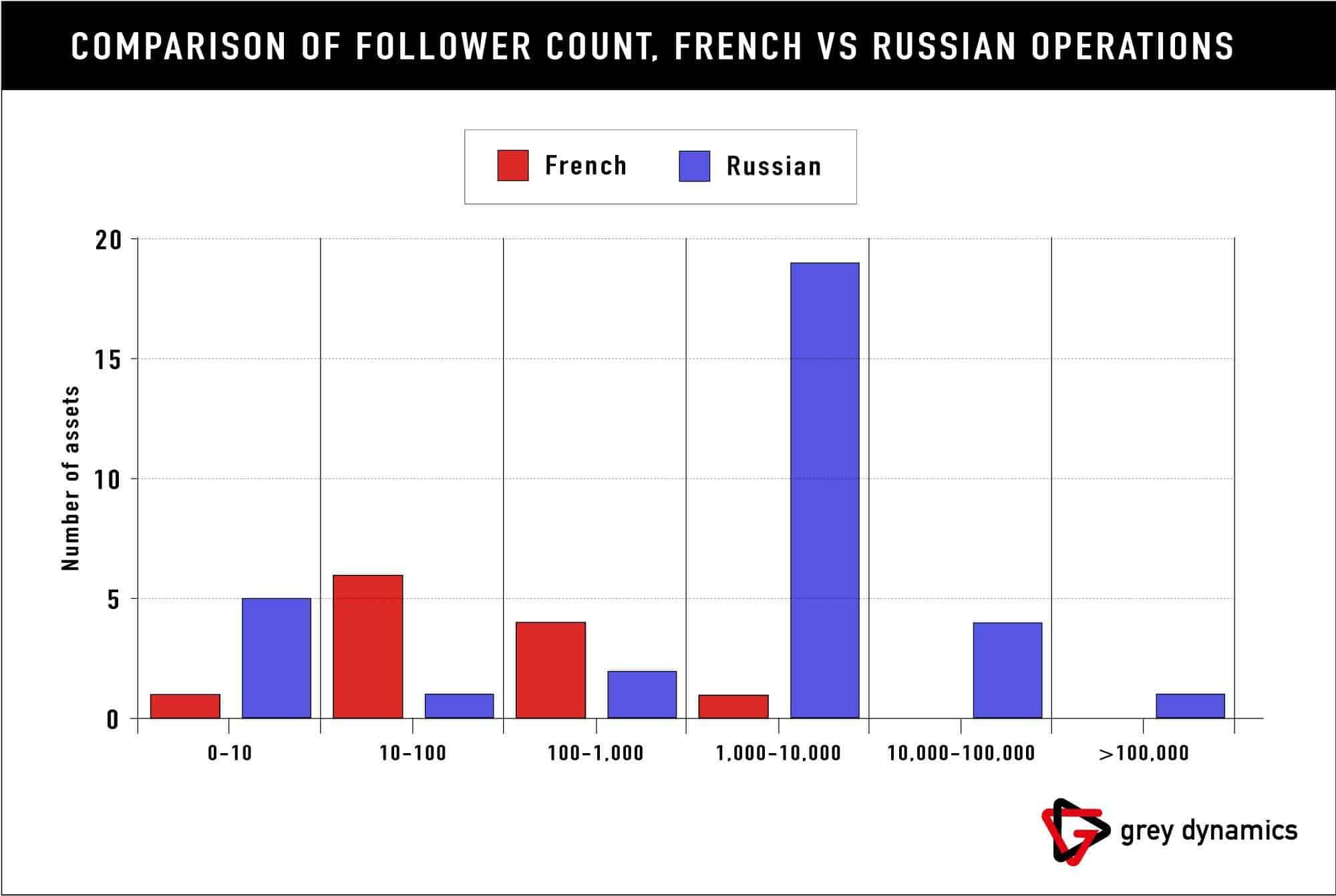

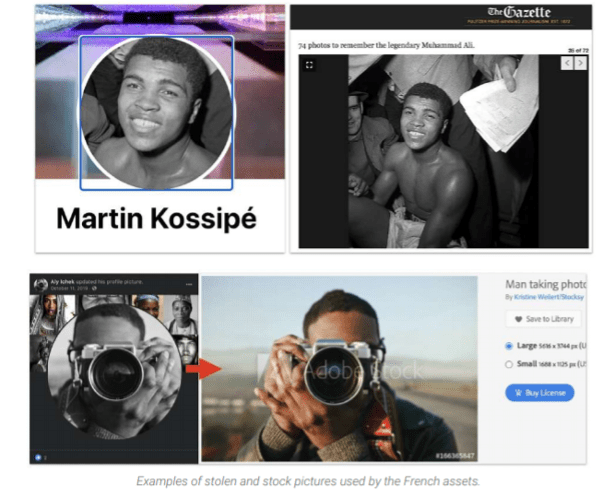

The Russian accounts removed in 2020 include 63 Facebook accounts, 29 Pages, 7 Groups and one Instagram account. The accounts were mainly established during January-March 2020, highly likely in response to the 2019 takedown. Russian operations in South Africa and CAR were highly active, with 140,000 followers on a South African page and over 50,000 in CAR. The main difference in Russian – French operations can be identified in the willingness of Russian operations to focus on electoral politics. France avoided this approach. CAR President Faustin-Archange Touadéra, a key Russian ally, was consistently elevated on these platforms. Simultaneously, Touadéra’s primary rival Francois Bozizé was consistently tarnished. Accounts with stolen photos and fake news outlets spread across the digital information landscape.

Russian operators even paid to promote their posts. The network became utilised to amplify each other’s posts, in line with social media algorithms to reach the widest possible audience. Posts would regularly praise Russian contributions to the region. The extent of the operations and the inclusion of local nationals supports the judgment that the Russian operation was more effective. This is also supported by the experience and emphasis of Russian actors regarding information campaigns in the cyber space compared to French operations.

French Campaign

Facebook’s removal of the French network included 84 Facebook accounts, 6 Pages, 9 Groups, and 14 Instagram accounts. One section of the network focused on Mali, an area formerly under French colonial rule (as is CAR). Since 2013, French and UN forces are active in Mali under anti-terrorism missions. Positive engagement through the network attempted to influence the receptivity of the public to their presence and impact. The French operation utilised Generative Adversarial Networks, an artificial intelligence model producing realistic imagery. Such imagery in profile pictures were used to add credibility to fake accounts. Mock cartoons were created, amplifying negative aspects of terrorists in Mali.

Contrary to the Russian operation, the French network did not focus on electoral politics. This can be interpreted as a desire for support for French troops rather than concessions from incumbent leaders. The French network did not match levels of engagement and followers enjoyed by the Russian network. French operations also attempted to boost authentic engagement through the inauthentic accounts, boosting each other’s content in groups. This attempt cannot be classed as significantly successful.

French operations were also targeting Niger, Burkina Faso, Algeria, Cote d’Ivoire, and Chad, albeit to a lesser degree. Contrasting with Russia, the “coordinated inauthentic behaviour” identified was a violation of Facebook’s policy. As Russia and France both have strategic interests in Africa, the intent for such operations is self-explanatory. The capabilities of the French operation proved less effective. Intent and capability aside, as well as the success, the consequences are arguably even more significant. Russia’s troll farms are well documented. Attempting to ‘fight fire with fire’ in this case not only fell short but provided credibility to Russian troll farm actions. This will highly likely encourage Russian operations to increase, interpreting a ‘resorting’ attempt, especially in CAR.

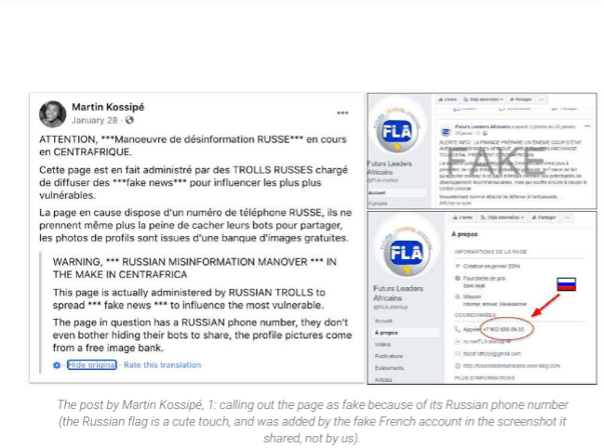

Trolls Collide

When competing interests collided in the CAR case, the approach from the networks were practically identical. Networks attempted to expose the other as ‘fake news’, an ironic tactic from fake accounts. Martin Kossipé, the leading fake persona of the French operation labels Russian operation content as fake news. This was a common tactic from both sides, attempting to expose each other on participating groups and pages. The operations resorted to comical satire, involving cartoon animations of stereotypes and ulterior motives in CAR involvement. Both operations falsely accused authentic accounts, highly likely by misinterpretation, to be fake. This undermined credibility of authentic behaviour in the cyber space and increases suspicion of widespread fake news.

In a peculiar turn of events, the networks began to support each other. This was done by sharing one another’s post on the online community chats. The intent behind this approach is not clear but has a realistic probability of being an attempt to avoid ‘fake news’ suspicion. The accounts even befriended each other. This was all during the ongoing information war between the networks. As information warfare increases, this case study on troll-on-troll activities may be an example of what is to come. Unfortunately, this approach will highly likely damage credibility of online discussions and deter potential contributors from engagement.

Image: Bryce Durbin (link)