1.0 Introduction

The Special Air Service (SAS) is the most elite special forces unit of the British Army. This `Tier 1´ unit specialises in a variety of roles, including counter-terrorism, hostage rescue, direct action, and close protection among others. Much of the information about the SAS is highly classified, and the British government or the Ministry of Defence (MoD) rarely comment on the unit due to the secrecy and sensitivity of its operations.

The unit currently consists of the 22 Special Air Service Regiment, the regular component, as well as two reserves, the 21 Special Air Service Regiment (aka Artists) and the 23 Special Air Service Regiment. They all belong to the United Kingdom Special Forces (UKSF) Directorate. Its sister unit is the Royal Navy’s Special Boat Service (SBS), which specialises in maritime counter-terrorism. Both units receive direct support from the Special Reconnaissance Regiment (SRR) for surveillance and reconnaissance purposes. These units are under the operational command of the Director of Special Forces (DSF).

In this article, we analyse the history of the unit, its purpose and organisation, and its most relevant operations.

2.0 Motto, Symbols and History

2.1 Motto

The motto of the SAS is “Who Dares Wins”. The motto is attributed to SAS founder Sir David Stirling. Among the SAS themselves, it is sometimes humorously corrupted as “Who cares [who] wins? (source).

2.2 Symbols

The emblem of the SAS is a shield consisting of a blade, hence the nickname of its operators “blades”, with a pair of wings behind it. This indicates its status as an airborne unit as its name suggests. Below this is the aforementioned unit motto. This is also the SAS identification symbol.

The flag of the SAS consists of the aforementioned emblem superimposed on two green and blue stripes.

2.3 History

2.3.1 Origins: The North African Desert

The SAS originates in the commando units created during World War II when Britain created several special units that undertook a variety of operations against the Axis. After the fall of France in June 1940, the British established a small but well-trained and highly mobile assault and reconnaissance force known as the Commandos (source).

The Special Air Service (SAS) was formed in July 1941 by David Stirling. An Army officer, he was first commissioned into the Scots Guards and later in the No. 8 (Guards) Commando. He originally called it the “L” Detachment, Special Air Service Brigade. Its main task was to conduct small-scale raids behind enemy lines in North Africa. Stirling gave it the “L” designation and the name “brigade” to mislead Axis forces into believing that this unit was a large parachute regiment.

The new unit initially drew its men from No. 7 and No. 8 Commando. Later, troops from No. 62 Commando (also called the Small-Scale Raiding Force or SSRF) joined. The unit focused initially on the North African campaign (1940-43). L Detachment´s first mission was in November 1941. It consisted of a parachute drop-in support of the Operation Crusader offensive, codenamed Operation Squatter. Due to German resistance and adverse weather conditions, the mission was a disaster losing a third of the unit. Its second mission however was a great success. Transported by the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG), it attacked three airfields in Libya, destroying 60 aircraft without loss.

(Source), (source), (source), (source), (source)

2.3.2 Operations in Europe

In September 1942, they renamed it 1st SAS, composed of four British squadrons, one Free French squadron, one Greek squadron and a Folboat Section. In January 1943, enemy forces captured Colonel Stirling in Tunisia and Paddy Mayne replaced him as commander. A few months later, in April, they reorganised it into the Special Raiding Squadron and undertook raids in Sicily and Italy alongside the 2nd Special Air Service, which came into existence in May 1943 in Algeria. The 2nd SAS was formed by renaming the SSRF.

In 1944, both units became part of the Special Air Service Brigade and were joined by several other units. In 1944, the SAS was composed of:

- 1st Special Air Service

- 2nd Special Air Service

- 3rd Special Air Service (2e Régiment de Chasseurs Parachutistes and later succeeded by 1st Marine Infantry Parachute Regiment)

- 4th Special Air Service (3e Régiment de Chasseurs Parachutistesand later succeeded by 1st Marine Infantry Parachute Regiment)

- 5th Special Air Service (later succeeded by the Belgian Special Forces Group)

- F Squadron (responsible for signals and communications)

The 3rd, 4th and 5th SAS were formed by renaming Free French and Belgian parachute units. The brigade’s formations took part in numerous operations, often behind enemy lines, from D-Day (June 1944) until the German surrender in May 1945. Shortly after the war, the government disbanded the SAS.

(Source), (source), (source), (source)

2.2.3 Dissolution and Reinstatement

With the end of the war, the British government saw no further need for this force and disbanded it on 8 October 1945. However, the following year, the MoD decided that it needed a long-term deep-penetration commando unit and they ordered the creation of a new SAS regiment as part of the Territorial Army (TA). On 1 January 1947, the Mod decided that the Artists Rifles, raised in 1860 and based at Dukes Road, Euston, would adopt the SAS mantle as the 21st (V) SAS Regiment (source).

2.3.4 First Operations

In 1951, the MoD deployed the Z Squadron of the 21st SAS during the Malayan Emergency (1948-60). That squadron fought under the name Malayan Scouts. In 1952 the regular army absorbed the 21st as the 22nd SAS Regiment. This is the only time a regular unit has been formed from a TA unit. Many of the early volunteers were from the Rhodesian SAS aka C Squadron and New Zealand SAS (NZSAS).

In 1959, the MoD created a third SAS unit, also a TA force, known as the 23rd SAS Regiment. This was a rebranding of the Reserve Reconnaissance Unit, the successor to MI9, whose members were experts in escape and evasion.

2.3.5 Solidification of the SAS

SAS troops deployed during the Dhofar Rebellion (1962-76) to help safeguard the ruling regime by fighting a guerrilla war against communist rebels in southern Oman. The SAS deployed also during the Indonesian Confrontation (1963-66) to resist Indonesian attempts to cross the frontier. It also mounted secret cross-border raids into Kalimantan to pre-empt Indonesian attacks. The SAS deployed during the Aden Emergency (1963-67) when they carried out covert operations against Arab nationalists in Aden City (Yemen) and against rebel tribesmen in the mountainous Radfan region.

The Government also deployed the SAS during The Troubles (1969-2007) to carry out several surveillance operations and ambushes against Republican terrorists in Northern Ireland. In 1980, the SAS was part of one of his most famous operations, the Iranian Embassy siege aka Operation Nimrod. This event saw a SAS unit rescue 19 hostages held by armed terrorists from the Iranian Embassy in London. In 1982, the Army deployed the SAS during the Falklands War, tasked with conducting covert surveillance of Argentine positions before the British landed and attacked the Pebble Island airstrip.

For much of the Cold War, the role of the 21 SAS and 23 SAS was to provide rearguard groups (stay-behind) in the event of a Warsaw Pact invasion of Western Europe. Together they formed the I Corps’ Patrol Unit. In the event of an invasion, this SAS Group would have been bridged, remaining behind to gather intelligence behind Warsaw Pact lines. The plan was for them to carry out target acquisition and thus try to slow the enemy’s advance.

2.3.6 SAS and the UKSF

In 1987, an era of change arrived for the SAS. That year, the British Command created the United Kingdom Special Forces (UKSF), when the post of Director of the Special Air Service (SAS) became Director of Special Forces (DFS). The MoD created the UKSF by assigning the DSF control of both the SAS and the Navy’s Special Boat Squadron. It also renamed it Special Boat Service (SBS).

Since then, the directorate has expanded by creating and unifying new units. In 2001, they created the Joint Special Forces Aviation Wing (JSFAW) which specialises in covert battlefield insertion and extraction. The UKSF formed the JSFAW by merging the 7th Squadron (RAF) and the 658th Squadron (Army Air Corps). In 2005, the UKSF created the Special Reconnaissance Regiment (SRR) to support the SAS, alongside the 18th Signal Regiment. In 2006, they created the Special Forces Support Group (SFSG) which serves as a quick-reaction force to assist SF missions. This might include large supporting offensives, blocking enemy counter-attacks or guarding areas of operation (source; source).

2.3.7 The SAS Today

After the Cold War, SAS units deployed during the Gulf War (1990-91) to hunt down and disarm mobile missile units. During this time, the SAS deployed three squadrons, A, B and D, being the largest SAS mobilisation since the Second World War. The SAS deployed in Bosnia (1992-95), as well as in Kosovo (1998-99) helping KLA guerrillas behind Serbian lines.

The regiment returned to Iraq in 2003 after deploying on a hostage rescue mission (Operation Barras) in Sierra Leone (2000). In Iraq, the SAS formed part of Task Force Black/Knight to combat the post-invasion insurgency. The SAS also heavily engaged against the Taliban in Afghanistan (2001-14). Here the 22 SAS (A Squadron and G Squadron) participated in Operation Trent (2001), the largest operation in its history, which included its first wartime HALO parachute jump (source).

In early 2003, a squadron consisting of the 21st and 23rd SAS was operating in the Afghan province of Helmand against Al Qaeda forces, focusing on long-range reconnaissance. In 2007-08, a squadron-sized sub-unit of 23 and 21 SAS deployed to Helmand to train Afghan police and work with intelligence services.

The role of British special forces has transformed over the years. They have gone from defeating Hitler and fighting insurgencies to their current task, fighting the global war on terror. Over the past two decades, the UKSF has cooperated with the US Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) in building a powerful counter-terrorist force. For example in 2005/2006, after the Iraq invasion, the SAS were integrated into JSOC. Here they focused on counterinsurgency efforts on combating al-Qaeda in Iraq and the Sunni insurgency alongside Delta Force (source).

3.0 Purpose

The SAS, along with the other British SF regiments, is designed to help in the “long war” as well as asymmetric war. This responded to the need for special forces of small, well-trained, and well-supported units operating on battlefields where combat lines are poorly defined and enemies mix among friends. The MoD understands these special forces as “force multipliers”, that is, small teams of operators can achieve results comparable to those of larger forces. of the (source; source).

The objective of the SAS remains broadly the same as in the 1940s, with the addition of the new needs of the 21st century. The main ones are:

- Surveillance,

- Reconnaissance,

- Intelligence gathering,

- Sabotage and attacks inside enemy territory,

- Support and influence,

- Counter-terrorism,

- Hostage rescue,

- Direct action (DA),

- Forward Air Control (FAC),

- Close Protection (CP),

- Offensive action against high-value targets.

Today, much of the surveillance and reconnaissance function falls to the SRR, a unit formed, organised, and equipped to carry out this activity. This has freed up 22 SAS, the SBS and the Support Group to focus on offensive action alongside influence and support.

Aside from these traditional tasks, the SAS focuses today on waging the global war on terrorism (the War on Terror). The SAS is therefore increasingly prepared for irregular and asymmetric combat, to operate on battlefields where battle lines are poorly defined and acting as ‘force multipliers’.

3.1 SAS Doctrine

The British SAS mission is very multifaceted, as its operators are highly skilled in specialised disciplines to carry out different types of very demanding missions. Its competencies are mainly oriented towards counter-terrorism, hostage rescue and covert raids. The SAS is also well-versed in surveillance and reconnaissance tasks, as well as intelligence gathering. In these tasks, it is supported by other elite UKSF units such as the SRR and SFSG. In addition, SAS operators are specially trained to conduct sabotage and attacks inside enemy territory, close protection (CP) and offensive actions against high-value targets.

This highly specialised and secretive unit is renowned for carrying out some of the most dangerous and challenging missions in the world.

The British SAS is the equivalent of the Delta Force, officially known as the 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta, of the US JSOC.

4.0 Organisation

The SAS are part of the United Kingdom Special Forces (UKSF), a directorate that manages the assigned joint capabilities of the three-armed services. The SAS is under the operational command of the Director of Special Forces (DSF), a senior role within the Ministry of Defence (MoD). The DSF is also the head of the UKSF, which reports to the so-called Strategic Command (StratCom), formerly known as Joint Forces Command (JFC). They are governed by the Permanent Joint Headquarters (PJHQ) which are located at Northwood Headquarters (source).

The SAS regional headquarters (RHQ) are located in Stirling Lines, Herefordshire, England.

4.1 Regiments

Given the nature of its work, there is little public or verifiable information about the SAS. The British government does not generally comment on matters relating to special forces.

The Special Air Service consists of three units, one regular and two army reserve (AR) units. The regular army unit is the 22 SAS Regiment and the reserve units are the 21 Special Air Service Regiment (Artists) (21 SAS(R)) and the 23 Special Air Service Regiment (23 SAS(R)). These are collectively known as the Special Air Service (Reserve) (SAS(R)) (source).

The SAS consist of the following units:

21 Special Air Service Regiment (Artists Rifles) or 21 SAS(R). HQ: Regent’s Park Barracks, London, England.

22 Special Air Service Regiment or 22 SAS. HQ: Stirling Lines, Herefordshire, England.

- ‘HQ’ Squadron

- A Squadron

- 1 Boat Troop

- 2 Air Troop

- 3 Mobility Troop

- 4 Mountain Troop

- B Squadron

- 6 Boat Troop

- 7 Air Troop

- 8 Mobility Troop

- 9 Mountain Troop

- D Squadron

- 16 Boat Troop

- 17 Air Troop

- 18 Mobility Troop

- 19 Mountain Troop

- G Squadron

- 21 Boat Troop

- 22 Air Troop

- 23 Mobility Troop

- 24 Mountain Troop

- L Detachment (R Squadron)*

23 Special Air Service Regiment or 23 SAS(R). HQ: Birmingham, West Midlands, England.

Most SAS operators (22 SAS) come from the Royal Marines or the Parachute Regiment. Unlike the regular SAS Regiment, the 21 and 23 SAS accept members of the general population without prior military service (source).

L Detachment

L Detachment (formerly known as Squadron R) is a territorial (reserve) unit directly attached to the 22 SAS. It consists of 22 SAS veterans and civilian volunteers created to support 22 SAS. It provides additional manpower and casualty replacements, unlike the 21 and 23 SAS which act largely as independent units with their command structure. L Detachment volunteers go through the same selection process as their regular 22 SAS counterparts (source).

(Source), (source), (source), (source), (source)

4.2 Squadrons

22 SAS normally has between 400 and 600 troops. However, we do not know for certain the size of the SAS(R) regiments. The organisation of the 22 SAS is as follows:

The regiment has four operational “sabre” squadrons: A, B, D and G. Each squadron consists of approximately 65 members under the command of a commander.

- Each squadron is divided into four troops, led by a captain, and a small headquarters section.

- Troops usually consist of 16 members (called “blades” or “operators”).

- Each patrol in a troop consists of four members (4-man patrols), led by a corporal. Each member of a troop possesses a particular skill, in addition to the basic skills learned during their training.

The primary skills are:

- Signals: Proficient in using various portable radio systems such as High Frequency (HF) Radio and Satellite Communications (SATCOM).

- Medic: Source of aid in the event of injury.

- Demolition: Expert in the use of explosives and how to identify points on a structure where charges are best placed.

- Forward Air Control (FAC): Trained in how to communicate with aircraft to attack ground targets.

- Linguistic: Proficient in languages to deal with natives in persuasion operations or liaison with foreign troops.

(Source)

4.2.1 Command and Troops

Command / HQ Element

The command is composed of officers and support staff:

- At the head of each squadron is the OC (Officer Commander), usually an Army major.

- The 2nd in Command (2iC) has the rank of captain.

- Operations Officer.

- Squadron Sergeant Major (SSM).

- Squadron Quartermaster Sergeant (SQSM).

- Staff Sergeant.

Troops

The four troops in each squadron specialise in four different areas:

- Boat troop: It specialises in maritime skills including diving using rebreathers, kayaks (canoes) and rigid-hulled inflatable boats and often trains with the Special Boat Service (SBS).

- Air Troop: It specialises in free fall parachuting and high-altitude parachute operations including High-Altitude Low Opening (HALO) and High-Altitude High Opening (HAHO) techniques.

- Mobility Troop: It specialises in using vehicles and desert warfare. They are also experts in an advanced level of motor mechanics to field-repair any vehicular breakdown.

- Mountain Troop: It specialises in Arctic combat and survival, using specialist equipment such as skis, snowshoes and mountain climbing techniques.

The British SAS follows a rotatory practice. Thus, each squadron (four in total) takes care of different tasks. The duty rotations of SAS squadrons consist of the following:

- Counter-terrorism: One squadron remains on counter-terrorism duty in the UK.

- Operational deployment: A second squadron is deployed.

- Contingency or “strip duty”: A third will prepare for deployment while undergoing short-term training.

- Training: The fourth will prepare for long-term training overseas, such as jungle or desert exercises.

In times of war, it is common for the SAS to deploy two squadrons. In peacetime, a SAS squadron often performs so-called “team tasks”. This consists of small teams deployed on a wide range of operations, such as training and advising foreign armies, or escort operations among others.

(Source), (source), (source), (source), (source)

4.3 Counter-Terrorist Wing

The British SAS has a sub-unit called the Counter-Terrorist Wing (CTW), also known as the Special Projects Team, that performs its counter-terrorism (CT) role (source). It is formerly called the Counter Revolutionary Warfare (CRW) Wing. The CTW is an expert in Close Quarter Battle (CQB), and sniper techniques and specialises in hostage rescue in buildings or on public transport (source).

4.3.1 Close Protection

The CTW includes a Bodyguard Cell, or Close Protection (CP), tasked with training SAS operators in VIP escort techniques.

Profiles

The teams of this unit specialise in different profiles according to the different scenarios:

- Military Overt Protection: They are most commonly seen when VIPs visit war zones. Bodyguards take on a distinctly military appearance and carry weapons in plain sight. In this scenario, the open profile intends to deter attack and ensure that the PC team can react with maximum firepower.

- Low-key Overt Protection: The CP team aims to blend in more with their surroundings. They wear civilian clothes, usually suits. Weapons are usually concealed. The CP team still maintains a visible presence around the VIP, who is free to interact with the public.

- Covert Protection: The bodyguards are not visible but remain close at hand on standby to react as needed.

Techniques and Procedures

The SAS has also developed several techniques, procedures and protocols when it comes to escorting. Some of the most well-known procedures to the public are:

- Route Reconnaissance: PC teams scout the planned routes of their VIP motorcades, looking for possible ambushes, bottlenecks and choke points.

- Venue Reconnaissance: As with the vehicle routes, an advance party of the team inspects any planned meeting place in detail. In the event of an attack, they establish emergency exits and rendezvous points in and around the site.

- Offensive Driving: In the event of an attack on the VIP convoy, they use the cars as weapons, ramming the attacking vehicles or assailants and breaching a barricade.

- Embussing/debussing: CP ensures that the VIP enters and exits the vehicle safely.

- Close-quarters battle (CQB): Personal protection may require the use of firearms in confined spaces, often surrounded by comrades and innocent bystanders.

4.4 Revolutionary Warfare Wing (RWW)

The RWW, or “The Wing”, is an elite group of hand-picked British SAS operators with the task of supporting Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) aka MI6 operations. In recent years the RWW has expanded and is now called “E Squadron“. The SIS also refers to the group as “The Increment”. It conducts special operations under orders from the SIS/Foreign Office. Its functions include acting as bodyguards and support for SIS agents, the extraction of SIS personnel, as well as so-called “black operations”.

(Source), (source), (source), (source)

4.5 Parachute Squadron

The SAS receives support from the Special Forces Parachute Support Squadron (Para Sp Sqn). The role of this squadron is to advise the UKSF Group on all operational, training and developmental aspects of military parachuting. The Parachute Support Squadron is responsible for providing operational support and training to UK Special Forces troops to enable parachute insertion across the full spectrum of parachute capabilities.

This is a subunit of the Airborne Parachute Wing (ADW), an RAF training unit that provides parachute training to all three British Armed Forces and is based in RAF Brize Norton (source).

4.6 Operations Research Wing

The SAS also has an Operational Research Wing. This wing is reportedly composed of a few experienced SAS whose job is to evaluate and develop new equipment, weapons and techniques. In collaboration with technicians and scientists from the MoD, the cell ensures that the Regiment remains at the cutting edge. The cell came up with the concept of stun grenades in the 1970s. These stun grenades, or “Flash Bangs”, have since been adopted by armies and police forces around the world (source; source).

4.7 Aviation Support

The 22 SAS receives air support from 658 AAC Squadron to carry out its domestic counter-terrorism role. The 658 Sq operates several Eurocopter AS365N3 Dauphin II. This squadron is part of the Joint Special Forces Aviation Wing (JSFAW), a component of the UKSF. The JSFAW is an RAF and Army joint service that coordinates providing aviation support to the UKSF (source).

5.0 Recruitment and Training

5.1 Recruitment

UK Joint Special Forces Selection is the selection and training process for candidates for the UK Special Forces: Special Air Service, Special Boat Service and Special Reconnaissance Regiment. Until the late 1990s, SAS and SBS candidates were selected separately. Since then, British SAS and SBS personnel have undergone a joint selection process culminating in the award of a sand-coloured beret to SAS personnel, after which SBS candidates undergo further selection for the title of Canoe Swimmer, and SAS personnel receive additional specialist training. SRR candidates go through the aptitude phase, before moving on to their specialised training in covert surveillance and reconnaissance.

The UK Special Forces do not recruit directly from the general public. The only exception is the SAS(R). For these units, applicants do not need previous military service but must be no older than 42 years 6 months when applying to join the Army Reserves (AR) (source).

5.2 Selection

All current members of the UK Armed Forces are eligible for selection into the Special Forces, but the majority of candidates historically come from the Royal Marines or the Parachute Regiment. Selections happen twice a year, once in summer and once in winter.

To be eligible for selection, a candidate must be under 32 years of age (30 for officers) and have served in the military for at least two years. They must also be recommended for service in the UKSF by their commanding officer (CO) (source).

The training and selection process for British SAS candidates lasts approximately 32 weeks (6 months). After completing this initial training, candidates join the regiment as troop soldiers, where they receive additional basic training related to their speciality. The entire training process for SAS personnel can take up to three years, depending on the availability of specialized training programs (source).

Briefing Assessment Course (BAC)

This five-day programme tests basic fitness and skills such as swimming and map reading. The swim test consists of a high-water entry (10m), and treading water for 9 minutes. After this, they must do 500m of timed swimming and then a 10m underwater swim to retrieve a small weight from the bottom of the water. Finally, candidates attend an interview individually about their motivation for joining the UKSF (source).

Phase 1: Aptitude

The second phase of selection is the endurance or fitness and navigation stage. It is commonly referred to as the “Hills Phase”. The hill stage lasts 4 weeks and takes place in the Brecon Beacons and Black Hills in South Wales. Candidates have to perform increasingly difficult loaded marches, navigating between checkpoints individually using only a compass and hand-drawn sketch map. It is the endurance part of the selection and tests not only the candidate’s physical fitness but also his or her mental toughness. To pass this phase, a high level of determination and self-confidence is vital.

The endurance phase culminates in “the long haul” or “Long Drag”, a 40-mile (64 km) trek carrying a 55-pound (25 kg) bergen, which they must complete in less than 20 to 24 hours. Candidates cannot use paths and trails.

Phase 2: Standard Operating Procedures and Tactics Course

The second phase of selection consists of 14 weeks of training in SF tactics, techniques and procedures, which is conducted at the candidates’ respective units, Stirling Lines for the British SAS, and RM Poole for the SBS. Soldiers learn advanced handling of weapons used by the UKSF, as well as weapons used by foreign armies and adversaries. They also learn exercises in patrolling, ambush, breaking contact, close target reconnaissance, demolitions, vehicle handling, close-quarters battles (CQB), battlefield casualties and dynamic firing. Candidates who cannot assimilate and apply these skills are RTU’d (Returned to Unit) (source).

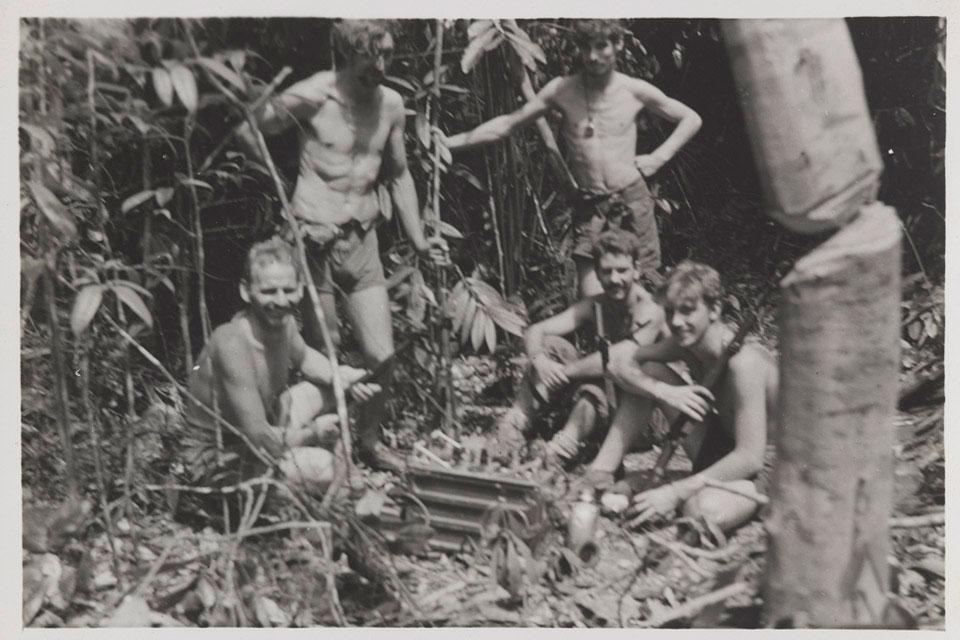

Phase 3: Jungle Training

After completing the above, the candidates must continue their training in the jungle. The training takes place in Borneo (Brunei) or Belize. The candidates learn the basics of survival and patrolling in harsh conditions. They are watched and assessed constantly by the Directing Staff (DS). SAS jungle patrols have to live for weeks behind enemy lines, in 4-man patrols, living on rations. This simulates long-range reconnaissance patrols (LRRP). Jungle training eliminates those who cannot endure the discipline necessary to keep themselves and their equipment in good condition while patrolling long distances in difficult conditions. Again, a mental component is put to the test, not just a physical one.

(Source), (source), (source), (source)

Last Phase: Escape & Evasion & Tactical Questioning

The small number of candidates who have passed endurance and jungle training now enter the final phase of selection. For the escape and evasion (E&E) part of the course, candidates receive brief instructions on proper techniques. This may include lectures from former prisoners of war or special forces soldiers who have been in real-world E&E situations. Candidates are then released into the field, dressed in WWII-period coats, with instructions to proceed to a series of waypoints without being captured by the hunting force of other soldiers. This part lasts 3 days, after which, captured or not, all candidates report to the TQ.

Tactical interrogation (TQ) tests the interrogation endurance of British SAS trainees. Interrogators treat them roughly, often forcing them to remain in “stress positions” for hours while throwing disorienting white noises at them. When it is their turn to be interrogated, they must only answer with the so-called “Big 4” (name, rank, serial number and date of birth). All other questions must be answered with “I’m sorry, but I can’t answer that question.” Failure to do so will result in failing the course. The interrogators will use all sorts of tricks to try to get a reaction from the candidates.

(Source)

5.3 After Selection

Typically, only 10% of candidates make it through the initial selection process. From a pool of approximately 200 candidates, most will drop out in the first few days, and fewer than 30 will remain at the end. Those who pass all the selection phases transfer to an operational squadron. The small number of men who make it through selection receive the coveted beige beret with the distinctive winged dagger insignia (below).

For applicants to the reserve component, 21 SAS and 23 SAS, the itinerary involves comparable elements, apart from jungle training. However, they do it by blocks, spread over a longer period, to suit the demands of the participants’ civilian careers. In October 2018, the recruitment policy changed to allow women to become members of the British SAS for the first time.

(Source)

5.4 Further Training

After surviving the tough selection process and snagging those SAS wings, the new SAS member jumps into a never-ending training phase. They’re always picking up new skills and perfecting the ones they’ve already got.

This continuous training includes tubular assaults (trains and buses), building assaults, aircraft assaults as well as counter-terrorism (CT) exercises. The SAS conducts much of their CT training in a specially constructed house at SAS HQ, colloquially referred to as the “Killing House”.

5.4.1 SF Parachute Course

This course is mandatory for all UKSF. Operators train in High altitude/high opening (HAHO) and High Altitude Low Opening (HALO). This is done with the Parachute Training Squadron, Airborne Delivery Wing (ADW) at RAF Brize Norton (source).

5.4.2 Swimmer Canoeist (SC3)

This course is for SBS personnel only and includes training in diving in all conditions, canoeing (often over long distances), underwater demolitions, beach reconnaissance and surveying techniques. Any candidate reaching this stage already belongs to the SBS. However, is in a probationary state and subject to dismissal (RTU) if it does not meet the standards (source).

6.0 Equipment

Apart from the standard range of weapons used by the British Army, SAS men have access to a wider selection of firearms and other weapons than the average British soldier. The publicly known weapons are the following:

6.1 Weapons

Guns

- Sig Sauer P226 / P228

- Glock 17(T) /19; local denomination L131A1/L132A1 and L137A1

Shotguns

- Remington 870; local denomination L74A1/A2

Submachine guns

- Sig Rattler

- HK MP-5

Rifles

- C8 Carbine; local denomination L119A1/A2 (source)

- KS-1 Carbine; local denomination L403A1 (Royal Marines) (source)

- SA80 A2 L85 (standard British Armed Forces rifle)

- M6A2 UCIW

- HK G3, HK 33/53, HK G63

Sniper Rifles

- HK417

- Accuracy International AWM; local denomination L115A3/A4

- Accuracy International AX50

Grenade Launchers

- M203

- UGL

- MK19 (installed in vehicles)

Anti-Tanks

Anti-Air

- Stinger

Explosives

- Claymore (portable anti-personnel mine)

Others

- Arwen 37 (tear gas canister launcher)

- Flash-Bang (stun grenade)

- ACOG Sights (rifle scope)

- AN/PEQ-2 (laser attachment)

- Laser Target Designators (LTD)

- Personal Role Radio (PRR)

- FIST Thermal Sight (FTS)

(Source), (source), (source), (source)

6.2 Personal Equipment

Not much information is available on the personal equipment of its operators except for photos. Some of its equipment is likely supplied by the Royal Marines:

Helmet

UKSF forces use the Ops-Core Future Assault Shell Technology (FAST) helmet, also known as the FAST helmet. This helmet is used by the Royal Marines (source).

Combat body armour

The standard Royal Marines combat ballistic/plate-carrying body armour is the C2R CBAV (Commando Ballistic Armour Vest), which forms the core of the Modular Commando Assault System (source).

Respirator

The Royal Marines use the General Service Respirator (GSR) which replaces the old S10 respirator. This respirator is used by the (source).

Uniforms

As part of the Future Commando Force program, the standard uniform for the Royal Marines since 2020 is the standard Crye Precision design with a MultiCam camouflage pattern. It replaces the Multi-Terrain Pattern Personal Clothing System uniform previously used, which continues to be used by the rest of the British Armed Forces (source).

6.3 Boats

SAS Boat Troops also use various types of assault craft such as Rigid Raiders and Inflatable Raiding Crafts. These are used for amphibious insertion/extraction, and demolitions.

6.4 Vehicles

The Special Air Service Mobility Troop uses a multitude of vehicles adapted to its mission. These are usually light and manoeuvrable vehicles that give their users great mobility. Some of these are:

- Land Rover WMIK

- Range Rover

- Supacat HMT 400 / 600 / 700

- LSVs (Light Strike Vehicles)

- Bushmaster IMV

- BV 206D ATV

- Quads

- Snowmobiles

The SAS is renowned for actively employing its legendary “Pink Panthers” (or Pinkies). These were mostly Land Rovers 110 adapted to the terrain and equipped with machine guns (source; source).

(Source)

7.0 Notable Operations

In the last decade, the SAS and other British special forces have actively engaged in covert operations in 19 countries. Due to the secret nature of its mission, its activity inside and outside the country is rarely public.

The following is a list of the most important British SAS operations after WWII:

From 1948 to 1979

- 1948-60. Malayan Emergency.

- SAS (Malayan Scouts) undertake jungle patrols and defeat a communist revolt in Malaya.

- 1962-76. Dhofar Rebellion.

- SAS troops help safeguard the ruling regime by fighting a guerrilla war against communist rebels in southern Oman.

- 1963-66. Indonesian Confrontation.

- The SAS resists Indonesian attempts to cross the frontier. It also mounted secret cross-border raids into Kalimantan to pre-empt Indonesian attacks.

- 1963-67. Aden Emergency.

- SAS units carry out covert operations against Arab nationalists in Aden (Yemen) and against rebel tribesmen in the Radfan region.

- 1969-2007. The Troubles.

- The SAS carried out several surveillance operations and ambushes against Republican terrorists in Northern Ireland.

- 1977. Operation Feuerzauber (Fire Magic).

- On the 18th of October 1977, SAS supported a German GSG9 commando operation to liberate Lufthansa Flight 181 from the Palestinian Terrorist group Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP).

(Source)

From 1979 to 2000

- 1980. Iranian Embassy Siege (Operation Nimrod).

- A SAS unit rescued 19 hostages held by armed terrorists from the Iranian Embassy in London. The operation raised SAS’s profile and strengthened its reputation.

- 1981. The Gambia Hostage Rescue.

- A small team of SAS men flew to Africa to rescue hostages and reverse a coup d’état.

- 1982. Falklands War.

- SAS troops conducted covert surveillance of Argentine positions before the British landed and attacked the Pebble Island airstrip.

- 1990-91. Gulf War

- The SAS hunted down and disarmed mobile missile units. This campaign included the famous Bravo Two Zero mission, whose objective was to find and destroy Iraqi Scud missile launchers. When the patrol was compromised, the 8-man SAS patrol attempted to escape. Unfortunately, 3 members were killed, 4 were captured and 1 managed to escape alone (Corporal Colin Armstrong, also known as “Chris Ryan”).

- 1992-2004. Bosnian War.

- The SAS was part of the NATO intervention in Bosnia-Herzegovina. During this time they captured several war criminals (source).

- 1998-1999. Kosovo War.

- The SAS actively assisted the KLA guerrillas behind Serbian lines (source).

(Source)

From 2000 to Today

- 2000. Sierra Leone Civil War.

- The SAS freed six British soldiers taken hostage during Operation Barras.

- 2001-2014. War in Afghanistan.

- The SAS participated in the initial invasion and remained active afterwards. The SAS mostly engaged in reconnaissance and hunting Taliban leaders. They also supported Afghan forces in retaking territory. British SAS also carried out Operation Trent, the largest operation in its history.

- 2003-2009. Iraq War.

- The SAS participated in the 2003 invasion of Iraq (as Task Force Black/Knight) and participated in subsequent operations afterwards. SAS integrated into JSOC and worked closely with Delta Force. Their main tasks were reconnaissance, infiltration, and capture/neutralisation of important members of the Iraqi regime. After the invasion, SAS focused on counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency (source).

- 2002-Today. Operation Enduring Freedom (Horn of Africa).

- Members of the British SAS and SRR deployed to Djibouti as part of the CJTF-Horn of Africa to conduct operations against Islamist terrorists in Somalia. They have also conducted surveillance missions.

- 2011. Libyan Civil War.

- 2014-Today. Military intervention against ISIS.

- The SAS were deployed to gather intelligence and evacuate Yazidi refugees. At least one squadron was deployed to Iraq and has reportedly been assisting Kurdish forces in northern Iraq. Some sources claim that SAS and US Special Forces fought alongside Kurdish forces during the siege of Kobane in Syria (source; source).

- 2023. Sudanese Civil War.

- Special forces including SAS took part in the rescue of two dozen British diplomats and their families from Khartoum in April 2023 after the outbreak of fighting in Sudan (source).

(Source)

8.0 Summary

The Special Air Service arose during World War II out of the need for a small but well-trained and highly mobile assault and reconnaissance force. Their success led the British authorities to consider such a unit as a highly useful tool to be deployed quickly and safely around the globe. Since then, and with the passage of time and the emergence of new threats, the SAS has constantly evolved, adapting to modern times. This is how the SAS, like the UK Special Forces Directorate, is now an expert in responding to the threat of terrorism.

The SAS remains today a lethal and flexible force on the battlefield, spearheading the elite units of the British Armed Forces. Its history, training and weaponry make this unit highly effective and efficient in its tasks. That is why the British military and political authorities entrust it with the most dangerous and delicate missions. In an increasingly hostile world, and given the continuing need to respond to threats, it is more than likely that the SAS will play an important role wherever British and allied interests lie.

9.0 Reading List Special Air Service

9.1. Rogue Heroes: The History of the SAS, Britain’s Secret Special Forces Unit That Sabotaged the Nazis and Changed the Nature of War

- Author: Ben Macintyre

- Publication Date: 2016

Why It’s Relevant

An officially authorized account of the SAS’s WWII origins—based on newly opened archives—that also reveals the core “rogue spirit” still shaping the Regiment’s modern-day missions (from counterterror ops to high-stakes raids).

9.2. Operation Mayhem

- Author: Steve Heaney (with Damien Lewis)

- Publication Date: 2021

Why It’s Relevant

While Heaney served in the Parachute Regiment/Pathfinders rather than the SAS, his account of post-9/11 British special ops shows the cross-pollination of tactics within UKSF. Offers insight into stealth infiltrations, small-unit raids, and the day-to-day challenges that SAS teams also face.

9.3. SAS Operation Storm: Nine Men Against Four Hundred

- Author: Roger Cole

- Publication Date: 2012

Why It’s Relevant

Follows SAS squadrons in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, spotlighting how 21st-century SAS operators balance reconnaissance, direct action, and rapid helicopter assaults in the world’s harshest conflict zones.

9.4. Zero Six Bravo: 60 Special Forces. 100,000 Enemy. The Explosive True Story

- Author: Damien Lewis

- Publication Date: 2013

Why It’s Relevant

Covers a dramatic 2003 Iraq operation widely attributed to SAS operators who found themselves trapped behind enemy lines. Highlights the Regiment’s hallmark improvisational skills and “never quit” ethos in large-scale ambush scenarios.

9.5. Task Force Black: The Explosive True Story of the Secret Special Forces War in Iraq

- Author: Mark Urban

- Publication Date: 2010

Why It’s Relevant

Reveals how the SAS joined forces with America’s Delta Force in a Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) framework post-invasion of Iraq, focusing on counterinsurgency and direct-action raids against al-Qaeda in Iraq.

9.6. Bloody Heroes: The Explosive True Story of a Band of Secret Warriors in Afghanistan

- Author: Damien Lewis

- Publication Date: 2007

Why It’s Relevant

Though slightly older, this account delves into SAS missions in Afghanistan, where small patrols faced both natural hazards (mountain peaks, harsh climate) and determined insurgents. Provides an unvarnished look at the Regiment’s early post-9/11 deployments.

9.7. The SAS 1983–2014

- Author: Leigh Neville

- Publication Date: 2016

Why It’s Relevant

Zooms in on SAS adapted to counterinsurgency in Afghanistan. Neville’s research-driven approach places SAS actions in the broader context of British operations—covering kit, tactics, and the real challenges on the ground.

9.8. Special Forces in the War on Terror (General Military)

- Author: Leigh Neville

- Publication Date: 2015

Why It’s Relevant

Neville’s comprehensive overview of global special operations post-9/11 explores how the SAS, SBS, and other Tier 1 units conduct manhunts, hostage rescues, and precision raids. Excellent for seeing how the SAS fits alongside allied forces (Delta, SEAL Team 6) in modern multi-national missions.